Overcoming negative moments in life does not simply happen.

For many immigrants, nowhere is this more true than in overcoming abusive relationships with a person they both love and fear.

Many immigrant who are victims of domestic violence and physical abuse feel trapped in their relationships.

It requires taking actions to change and the courage to take those actions.

They worry that without their partner, no matter how badly they are mistreated and harmed, there is no path to permanent residence.

They’re wrong.

Immigrants, who are victims of domestic violence, often face several barriers to seeking help, including:

- Absence of English fluency and cultural differences

- Fears about immigration status and deportation

- Lack of knowledge about community services available to them

- Restrictions on access to housing shelters and medical facilities

Domestic violence, in short, is a relationship between a perpetuator and a victim. It can happen to anyone, but it is typically committed by someone who has significant power or control over the victim.

Domestic Violence Green Card Options

According to recent studies of domestic violence, 49% of immigrant women have suffered abuse at the hands of their intimate partners.

Among abusive U.S. citizen and lawful permanent resident husbands who could have filed immigration papers for victims, 72.3% never filed documents to legalize their wives’ status.

Yet, there are several potential roads to green cards for immigrants. For immigrant victims of domestic abuse, two paths stand out.

First, the Violence Against Women Act.

Second, the U Visa program.

Under VAWA, the Violence Against Woman Act, an immigrant spouse who suffered battery or extreme cruelty inflicted by a U.S. citizen or permanent resident can file a self-petition (without her spouse) to seek permanent residency status.

Under the U Visa guidelines, an immigrant who is the victim of a crime – who has suffered substantial physical or mental abuse related to the criminal activity – can likewise apply for immigration benefits.

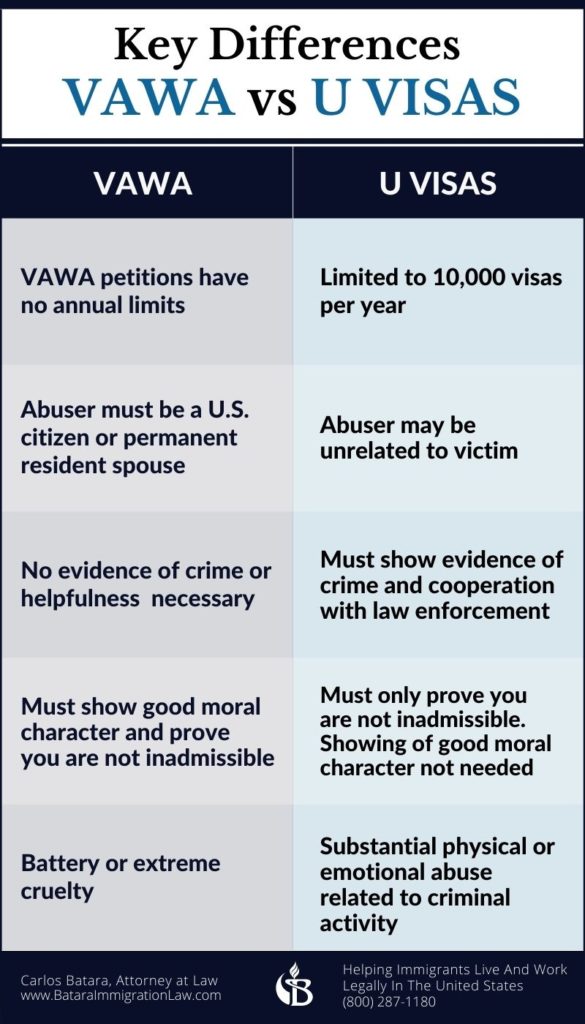

5 Differences Between VAWA And U Visas For Immigrant Victims Of Domestic Violence

There are five important differences between the two programs.

- Limits On Grants Per Year

- Marriage Requirements

- Cooperation With Law Enforcement

- Good Moral Character

- Proof Of Harm And Abuse

This means in some cases an abused immigrant will quaify for one program, but not the other.

For instance, a victim will be eligible for protection under the Violence Against Women Act, but will be ineligible for benefits under the U Visa program. Or vice versa.

Of course, the programs are not exclusive. Some individuals can seek relief under both programs,

Nonetheless, given the particular facts of an abused immigrant’s situation, one program may offer the easier or better solution for such persons to pursue.

Both programs have two steps to applying for a green card on one’s own, without relying on an abusive U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident.

- The first step is to file an initial petition. For VAWA, Form I-360 must be submitted to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services with supporting evidence. For U Visa, Form I-918, must be submitted with supporting evidence.

- The second step occurs after the petition has been approved. Both programs mandate the filing of Form I-485, Application To Register Permanent Residence Or Adjust Status.

Let’s dive into the differences.

1. Limits On Grants Per Year

First, the Violence Against Women sets no yearly limits on how many immigrants can win their cases. The U Visa program, on the other hand, is limited to 10,000 grants per year. As a result, it takes much longer for U Visa grantees to complete the entire process to permanent residence.

VAWA I-360 Self-Petitions

Based on my experience as a green card lawyer, the VAWA process takes about 18 to 24 months from start to finish – from the date a self-petition is filed to a final decision whether to grant or deny your petition.

In most cases, as a first step, USCIS issues a Prima Facie Determination to immigrants who appear to qualify for VAWA about six months after their initial filing.

This is a temporary notice. It grants immigrants deferred action, that is, protection against deportation and enables them to receive work authorization while their petition is pending.

There is no limit on how many I-360 self-petitions can be approved by the government each year.

Once a VAWA self-petition is approved, immigrants can apply for permanent residence if their priority date is current. Those who are or were married to United States citizens may be classified as immediate relatives and able to file for adjustment of status without futher delay. Battered immigrant spouses who fall under other immigrant beneficiary categories will not to be able to file for a green card until a visa is available for them.

U Visa I-918 Petitions

Because the U Visa program has a cap of 10,000 visas per year, once the cap is reached, the rest of the cases are rolled over to future years.

The U Visa program moves very slowly because of the grant limitation. The U Visa program at present is well over 200,000 cases behind.

To partially offset the lengthy wait, USCIS grants deferred action to immigrants who have gone through the application process and whose cases have been approved, but for whom no visa is yet available. Once immigrants get deferred action, they are eligible to apply to USCIS for work authorization.

Unlike the short VAWA Prima Facie Determination process, the U Visa interim waiting period for deferred action would often take up to six years. Recently, the government implemented a new Bona Fide Determination (BFD) process to help U Visa applicants receive work authorization and deferred status protection against deportation sooner.

At present, it is unknown how long it will take USCIS to issue BFD decisions.

Further, due to the long delay before approvals, under the new procedures, work permits and deferred action will be granted in four-year increments. At the time of renewal, the government will update its information about each U Visa applicant and background checks.

All-in-all, unless USCIS modify the annual limits, immigrant I-918 petitions may not be approved for 20 years.

Once the petition is granted, U Visa holders have to spend three more years in the United States before they can apply for adjustment of status to finally become a lawful permanent resident.

The examples in this article center on immigrant women victims of domestic violence. However, both programs, VAWA and U Visas, apply equally to abused immigrant males.

2. Marriage Requirements

Second, under VAWA, the immigrant must have been married to the abuser, and not have been divorced longer than two years before applying (except in immigration court cases). The U visa, on the other hand, has no such requirement, which means it can used when the abuser is merely a fiancé or casual companion.

This is a major distinction between the two programs.

Take the situation of a female who lived with a United States citizen or permanent resident for several years. They did not marry. They had two children. During their time together, he consistently slugged her with closed fists and would not let her have friends or access to bank accounts without his permission.

Under the Violence Against Women Act, these facts would enable her to file a self-petition if they were married during any of this abuse. She was not married. She is precluded from VAWA protection and benefits.

Under the U Visa, even if they were not married, she can still go forward with seeking immigration benefits as long as she actively cooperated with law enforcement, as noted below.

3. Cooperation With Law Enforcement

Third, under the U Visa, which centers on criminal activity, the immigrant must have cooperated with law enforcement to prosecute the abuser. VAWA imposes no such limitation.

To illustrate the differences, let’s briefly look at a situation where an immigrant spouse has been abused physically, mentally, and financially. During the course of the relationship, she was hit over the head with a telephone, not allowed to visit with her relatives, and forced to have non-consensual sexual relationships. She never reported any of these actions to law enforcement authorities.

Under VAWA, the victim could still proceed forward. The abuse and cruelty she suffered are both extreme. Of course, there will still be a problem of proof. If the violence can be shown, she stands a chance to win her Violence Against Women Act case.

But she never reported a crime being perpetuated upon her. She did not seek assistance from a housing shelter or advice from a non-profit center, groups that might have helped her report the incidents of violence and cruelty. This means desipte the level of violence committed by her spouse, under the U Visa program, she does not meet the threshold for filing an application.

Because there is no crime, there is no cooperation in prosecuting a crime. The request for U Visa benefits will be denied.

4. Good Moral Character

Fourth, the VAWA self-petition process mandates evidence of the immigrant’s good moral character, whereas no such showing is necessary under the U Visa.

Under the Violence Against Women Act, an abused immigrant has to provide records from everywhere they lived. If the applicant has committed a crime or been arrested, this might adversely affect their chances of prevailing. On the other hand, if the conviction is related to threats or coercion imposed by the spouse who perpuated the domestic violence, such actions often excuse the negative blemishes.

To be granted a U Visa, a good moral character showing is not required. But the issues of arrests and convictions will arise when the U Visa beneficiary later tries to seek permanent residency benefits. They are going to have to re-address those issues.

By then, the U Visa beneficiary should have taken actions that demonstrate rehabilitation and remorse, actions that depending on the seriousness of the offense, coupled with their abuser’s domination and control, may negate the impact of the immigrant’s criminal past. In this regard, the immigrant victim’s work with law enforcement could be strong evidence of rehabilitation.

5. Proof Of Harm And Abuse

The fifth point of differentiation between VAWA and U Visa cases is the proof of harm and abuse.

In short, what is the degree of harm required for each program?

Under the Violence Against Women Act, the requirement of harm that must be proven is battery or extreme cruelty.

Battery is a physical act that results in harmful or offensive contact with another person without that person’s consent, is not an absolute requirement. This includes actions like slapping, hitting, punching, pushing, kicking,

These actions are not necessary to win a VAWA case. Extreme cruelty can be enough in many cases.

Extreme cruelty includes ridculing the immigrant and calling her names in the presence of family and friends, having affairs with other women, not allowing her to work, or as noted earlier, preventing her access to bank accounts or the use of telephones.

Under the U Visa regulations, an applicant has to show substantial physical or mental abuse related to or caused by criminal activity.

This means if the criminal activity, for which a U Visa applicant cooperates with the police or sheriff’s department for prosecution purposes, does not cause a significant degree of harm for the immigrant, she will not qualify for a U Visa.

To demonstrate “substantial” proof of victimization, reports from medical physicians, mental health therapists, psychologists, housing shelther counselors describing the physical and emotion trauma are usually required.

Two Roads To Green Card Freedom For Immigrant Victims Of Domestic Violence

As this article has tried to illustrate, there is hope for immigrant victims of domestic violence.

Both VAWA and U Visa applications can help abused immigrants escape physical and mental mistreatment, and gain freedom from their victimizers.

But the strictness of the requirements for each program should not be under-estimated.

In most instances involving intimate partner abuse, immigrant victims will need to seek to seek out professional assistance to guide them past their trauma and fears.

With compassionate advice and conscientious support, abused immigrants can win permanent resident status and start a new life.

Hopefully, you, or anyone you know, will never need to use these programs.

But should that happen, I really, really wish you the best.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics