Sponsoring family members to live in the U.S. has been a central tenet of immigration law for over 50 years.

Contrary to chain migration rhetoric, immigration rules do not facilitate expedited passage of unlimited numbers of distant relatives through America’s ports of entry.

Rather, family-based applicants from abroad experience a slow and tedious process.

Over 28% of immigrants granted green cards from abroad last year had been waiting 10 years or longer for their interviews.

In this article, we’ll explore their plight.

What Is Family Unity?

In short, family unity is the foremost principle underlying immigration law.

The concept rests upon a realization that families are the bedrock of society. Policies that bring immigrant families together provide emotional, psychological, economic, and social stability to local communities.

Family unity was codified in 1965 when Congress passed the Immigration And Nationality Act – legislation crafted to eliminate a national origin quota system that favored European immigrants over those from other parts of the world.

The 1965 Immigration Act created a “family preference” quota system.

By allocating visas based on family sponsorship, the legislation promoted both diversity of country origins and unification of immigrant families.

How The Family Unity System Works

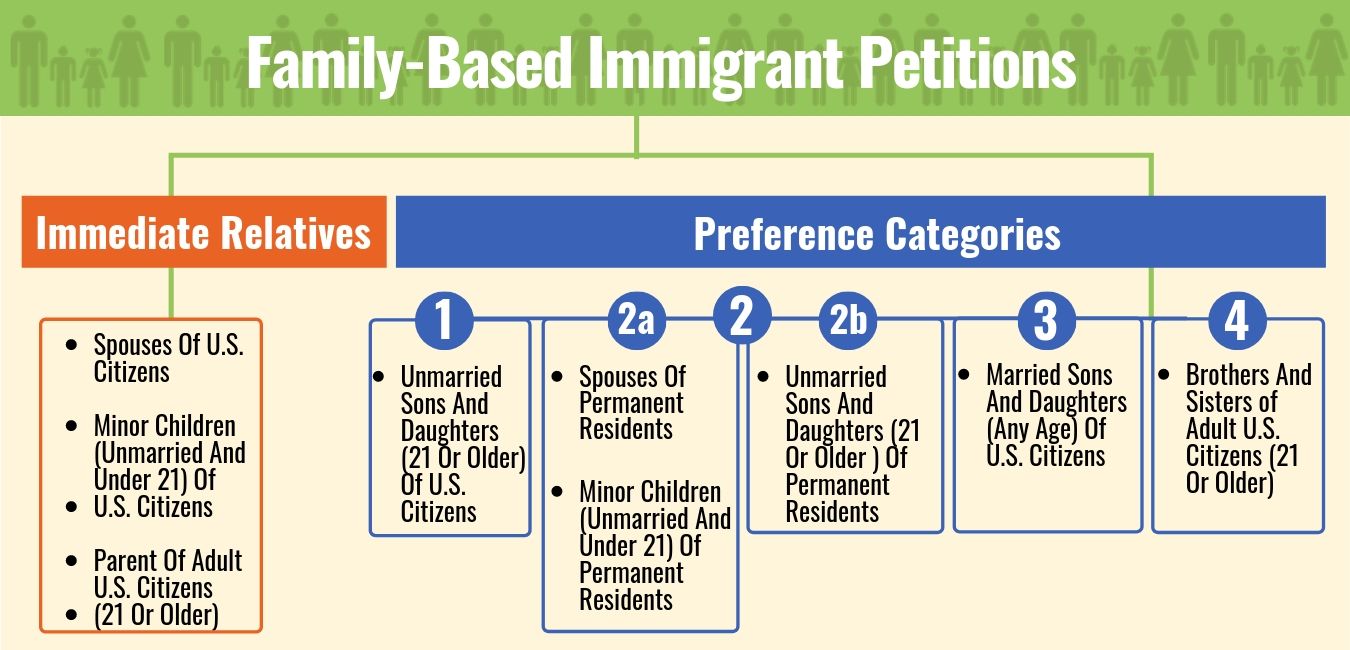

The family-based immigration road to permanent residence is divided into two broad classifications.

Immigrants who fall under the first classification are deemed “immediate relatives”. This grouping includes the spouses, minor children (unmarried and under 21), and parents of U.S. citizens.

Many of these individuals are able to pursue adjustment of status to permanent resident within the United States.

Curiously, when the family unity system was enacted, other close relatives of United States citizens – children over 21, children under 21 who are married, brothers and sisters – were not classified as immediate relatives.

Instead, they were placed in a different grouping. Known as the “family visa preferences” system, this classification aligned them with certain relatives of permanent residents who qualify to seek green card benefits.

What Are The Immigrant Visa Preference Categories?

The family preferences system divides eligible relatives into four distinct groups:

- First Preference: The immigrant is an unmarried son or daughter, over 21, of a U.S. citizen.

- Second (2A) Preference: The immigrant is a spouse, or an unmarried child under 21, of a lawful permanent resident.

- Second (2B) Preference: The immigrant is an unmarried son or daughter, over 21, of a lawful permanent resident.

- Third Preference: The immigrant is a married son or daughter, any age, of a U.S. citizen.

- Fourth Preference: The immigrant is the brother or sister of a U.S. citizen 21 or older.

What’s the biggest difference between those in the “immediate relatives” category vis-a-vis the “family preferences” category?

Immediate relatives are not subject to a quota. This means there are no limits on the number of green cards that can be issued to immediate relatives of U.S. citizens.

How Large Are The Backlogs in The Immigration Family Preference Categories?

On the other hand, there are annual limits on the number of immigrants who can receive green cards via the preference system. 226,000 is the current cap for the four categories combined, set by Congress in 1990.

Each of the four family preference system sub-categories have a different quota.

According to the CATO Institute, a public policy research organization, nearly 3.7 million immigrants languish in waiting lists for family-based visa preference categories:

- 1st Preference Backlog – 261,704 (Annual Quota: 23,400) (Country Limit: 1,638)

- 2A Preference Backlog – 145,861 (Annual Quota: 87,900) (Country Limit: 6,153)

- 2B Preference Backlog – 24,231 (Annual Quota: 26,300) (Country Limit: 1,841)

- 3rd Preference Backlog – 689,924 (Annual Quota: 23,400) (Country Limit: 1,638)

- 4th Preference Backlog – 2,249,722 (Annual Quota: 65,000) (Country Limit: 4,550)

These backlog numbers do not include immigrant family members living in the United States waiting to adjust their status to lawful permanent residence. Rather, these totals reflect only immigrants waiting outside the United States for a visa to become available.

Complicating matters further, only 7% of all preference category visas can be given to immigrants from any one country.

This produces a jughead system.

With over 180 nations, if each country sought their maximum total of visas in a given year, this would equal over 1,000%.

In short, the 7% limit per country is only an allowable maximum, not a guaranteed number, of visas available to that country.

This means even if immigrants from a particular country have not used up their nation’s 7% annual limit for the year, they can still end up on a waiting list during the next year. (In some instances, cross-chargeability provisions allow a husband or wife to to “borrow” visas from their spouse’s country of birth.)

What countries have the largest waiting lists?

It varies from category-bycategory.

This graph illustrates the top 10 backlogs by country in each of the family visa categories.

Cracks In The Family Preference System

As the visa preference numbers illustrate, our immigration system for family members trying to legally enter from abroad needs to be revamped.

In a nutshell, here’s how the system works:

- Family members residing in the U.S. apply for their relatives living abroad. If the sponsoring family member falls within the “family preference” category, the relative’s ability to immigrate depends on the system of quotas for family-based visas.

- Over time, the quota of visas available to immigrants in the family preference categories has not kept up with the demand for requested visas. Since the system is based on a “first come, first served” process, newer applicants are placed in a waiting line.

- Every year, the visa waiting lines have grown longer. The country quotas have remained static, even though immigration patterns, among various countries, have changed

- This has led to a huge backlog of immigrants waiting to reunite with their family members, especially those from countries with greater ties, and hence greater migration flows, to the United States.

- Immigrants from four countries – China, India, Mexico, and the Philippines – experience the longest waiting periods. Their waits are directly linked to the limits imposed on the amount of visas granted per country. For instance, a Mexican child over 21 of a U.S. citizen or a Filipino brother of a U.S. citizen must wait 15 – 20 years to complete the immigration process.

- Lawful permanent residents, attempting to sponsor their relatives, are less fortunate than U.S. citizens. Many of them, after having waited several years to enter the U.S. legally, precede their spouse and children in order to find work and save money. Since their sponsorship falls under the family preference system, quotas and backlogs can delay the reunification with their relatives for more than a decade.

- These sorts of deficiencies often cause immigrant families to despair and resort to entering without permission, rather than wait countless years for legal admission. Some estimates show 50% of immigrants living in the U.S. without proper authorization have been approved for family-based visas but are trapped in the preference category backlog.

- This breakdown in the family unity system, coupled with the government’s inability to forge a plan for comprehensive immigration reform, has inspired a misguided deportation policy. Almost 400,000 immigrants per year have been removed from the U.S. since 2009.

When the family unity process is stripped down to its essentials, as above, various potential solutions emerge.

Increasing the amount of family visas, redefining family preference categories, placing caps on waiting times, and adjusting per country visa limits are just a few which come to mind.

No More Excuses For Half-Baked Family Immigration Solutions

Given the animosity of immigration reform opponents, truncated stopgap measures, like I-601 hardship waivers, are no longer politically justifiable – if they ever were.

Such measures, in my perspective as a Riverside immigration attorney, are a dim reflection of true family unity.

The failure to holistically update our family-based immigration system for several decades mandates that immigrant advocates cannot allow candidates for public office to sandbag family unity concerns any longer.

Family visa backlogs continue to grow. The waiting times for green card interviews are getting longer.

Meanwhile, those currently in charge of our immigration policies insist on tightening regulations for lawful admissions. Such actions keep families apart, not bring them together.

In other words, it’s time to restore family unification to the forefront of the immigration debate.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics