Defeat in law, especially immigration law, should be taken with a grain of salt. It is not uncommon for policies and principles to change over time.

“When one door closes”, Alexander Graham Bell once noted, “another often opens.”

He could have been talking about the Temporary Protected Status program.

On June 7, 2021, the Supreme Court denied the eligibility of TPS beneficiaries to seek adjustment of their status to permanent residence without leaving the United States.

Is their hope of becoming a lawful permanent resident now gone forever?

Asserting the Sanchez v. Mayorkas decision was a major step backwards, many immigrant advocates claimed immigrants living in the United States for humanitarian reasons cannot win green cards if they illegally entered the country.

The truth, though distasteful, is not so absolute.

Hyperbole aside, solely from a legal perspective:

- Some immigrants who entered the United States, lawfully or unlawfully, for humanitarian reasons can still win permanent residence status.

To be clear, the Sanchez decision only affects TPS grantees who entered the U.S. without inspection.

More specifically, the Court held that a grant of TPS is not the equivalent of an inspection, admission, or parole into the United States.

This means if you were inspected and admitted to the United States on a tourist or other type of nonimmigrant visa, and later won TPS benefits, you can still become a green card holder through adjustment of status without returning to your home country.

In addition, the political battle over the proper parameters for the Temporary Protected Status program is far from over.

On June 18, 2024, President Biden announced a new Parole program for spouses of U.S. lawful permanent residents. This program will affect many TPS beneficiaries who may be eligible for earning a green card.

Of course, there are legal issues whether a TPS beneficiary can or should apply. Here is a short guide to parole in place for TPS beneficiaries.

What Is The Significance Of The “Inspection And Admission Or Parole” Provision?

What is the practical impact of the “inspection and admission or parole” provisions of immigration law on TPS recipients?.

Why do immigrant advocates consider the Supreme Court decision a major setback?

Here’s a brief explanation provided by Patrick Taurel, writing for Immigration Impact.

Only individuals who were “inspected and admitted or paroled” into the United States by an immigration officer may apply for LPR status from inside the United States.

Many of those who were not “inspected and admitted or paroled” into the United States (i.e. those who crossed the border without passing through an official checkpoint) must leave the country to have their paperwork processed by the U.S. consulate office in the immigrant’s last place of residence abroad to obtain LPR status.

This departure, though, can trigger harsh penalties that can strand immigrants abroad for months, years, decades, and sometimes forever.

This leaves many TPS recipients, including those with U.S. citizen spouses, essentially fenced into the United States because departing to obtain LPR status means running a risk of triggering the aforementioned penalties or of encountering the dangerous conditions that merited the TPS designation.

For many immigrants trapped in such circumstances, the only possible solution will be to seek a family unity I-601 waiver based on extreme hardship to their qualifying relatives.

Although the exact number of TPS beneficiaries who will be adversely affected by the Supreme Court decision is not known, the total could exceed 300,000 individuals.

And that’s only counting immigrants who have been designated for TPS status over the past five years.

The Supreme Court ruling will also negatively impact many more persons who obtained Temporary Protected Status protection between 1990 and 2015 from now-defunct TPS programs and have continued to live in the shadows of American society without lawful permission.

To say the least, I-601 waivers present formidable obstacles to victory, and increase the likelihood of permanent family separation.

Legal And Political Roots Of

The Supreme Court Decision

There are two reasons the Supreme Court input became necessary.

First, the legal battle over the meaning of “inspection, admission, and parole” for grants of temporary protected status.

For a decade prior to the Supreme Court decision, TPS recipients lived in a state of legal confusion. Federal courts could not reach a consensus on this issue – an issue crucial to the dreams and hopes of living together in the United States for many families.

Does a grant of Temporary Protected Status constitute a legal admission, inspection, or parole?

The answer, for far too long, was “It depends”.

It depended, in large part, on where you lived.

The Supreme Court decision put an end to that ambiguous answer.

Second, poor political foresight – dating back to the origin of the Temporary Protected Status program.

As its name implies, TPS was created to provide recipients with a temporary safe haven during their homeland’s crisis.

But Congress never set a cap on the length of the “temporary” status. (In fact, any cap would have been arbitrary and based on speculation.)

Nonetheless, the “temporary” should have been addressed.

Ostensibly, the re-review process of the conditions existing in TPS-designated countries, every 18 months was designed in part to protect the temporary nature of the program.

Yet, it was foreseeable that the longer a country was designated for TPS, immigrants from there would develop family and community ties in the United States – making the sudden termination of their TPS designation and forcing their removal back to their homeland an un-humanitarian way to handle the end of a humanitarian program.

In this regard, construction of a legal path to permanent residence should have been built into the TPS framework from the outset.

Designing a bridge from TPS to permanent residency if not for all, at least for some temporary protected status grantees, is not that difficult an endeavor.

A waiver, based on criteria set by Congress, for TPS beneficiaries from countries whose status were terminated, would have eliminated the need for the Sanchez case and millions of dollars spent litigating the case in federal courts over the past decade.

Prelude To The Supreme Court Decision: The Judicial Split Of Opinion On TPS

For nearly 10 years before the Supreme Court decision, TPS law was unsettled.

Beneficiaries under the Temporary Protected Status would renew their applications every 18 months. They hoped the grant of TPS would one day entitle them to seek adjustment of status to lawful permanent residence here in the U.S., without having to under go the more rigorous process of attending interviews in their home nations.

The division among federal courts was 20 – 9 – 21.

A legal path to winning legal residency for TPS holders via adjustment of status existed in 20 states.

The highest federal court for nine states reached a contrary result.

TPS immigrants living in the other 21 states were in limbo, unsure how their highest courts would rule. Without a decision allowing a direct path from TPS to permanent residence, prudence dictated taking the latter approach.

Due to the judicial severance, complicated scenarios loomed just around the corner.

- For instance, could a TPS grantee residing several years in one state, like Alabama, where no direct path to permanent residence existed – suddenly move move to California and win green card status?

- Would a TPS beneficiary who had lived in California for many years not be extended the same courtesy if she moved to Alabama?

From a legal perspective, the federal deadlock was untenable.

Thus, the Supreme Court as referee entered the dispute.

The Emergence Of A Divided Bench

Courts In Favor Of Granting TPS Beneficiaries

A Path To Permanent ResidenceOn March 31, 2017, the Ninth Circuit held that under Temporary Protected Status, a TPS recipient is deemed to be in lawful status and has satisfied the requirements of inspection and admission for the purposes of adjustment of status.

This means if your case was held in the Ninth Circuit region, you might be eligible to obtain lawful permanent residence in the United States and not need to seek a green card through consular processing in your home country.

The Ninth Circuit decision, Ramirez v. Brown, covered Alaska, Arizona, California, Hawaii, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oregon, and Washington.

On October 26, 2020, the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals adopted a similar legal position in Velasquez v. Barr, It has jurisdiction over cases arising in Arkansas, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Dakota, and South Dakota.

The same outcome was reached in the Sixth Circuit. In Flores v, USCIS, the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, which oversees matters in Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee, agreed TPS recipients should be considered as being in lawful status when they are seeking adjustment of status.

Courts In Opposition To Granting TPS Beneficiaries

A Path To Permanent ResidenceOn the other hand, in Serrano v. U.S. Attorney General, the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals, with judicial authority over cases arising out of Alabama, Florida, and Georgia, reached the opposite conclusion.

On July 22, 2020, in Sanchez v. Secretary U.S. Department of Homeland Security, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals likewise held the granting of temporary protected status does not qualify as an admission into the United States. The Third Circuit presides over cases arising in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and Delaware.

And shortly after the Velasquez case, on November 23, 2020, the Board of Immigration Appeals held an immigrant is considered to be admitted for purposes of adjustment of status (a) only while their TPS status remains valid and (b) only within the 6th, 8th, and 9th Circuits in Matter of Padilla Rodriguez.

On February 3, 2021, in Rodriguez Solorzano v. Mayorkas, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals joined the legal choir arguing that TPS does not cure the bar to adjustment of status, because a grant of TPS does not constitute a lawful inspection and admission. The Fifth Circuit has jurisdiction over cases from Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas.

Potential Problems For TPS Holders Granted Green Cards In The 6th, 8th, And 9th Circuits

Before the Sanchez decision, USCIS offices in the 20 states covered by the Sixth, Eighth, and Ninth Circuit Appellate Courts were granting adjustment of status applications to TPS residents of those states. Now, all such applications still pending will be denied.

Will these denials lead to the issuance of a Notice To Appear at Immigration Court to face deportation charges?

A more ominous scenario is the effect of the Supreme Court decision on already approved green card applications.

- Will the government attempt to rescind the permanent resident status of TPS holders who won their cases under the overturned federal court decisions?

- And even if the government does not take such steps, will this affect future attempts of such TPS beneficiaries to become naturalized citizens on the grounds that the grant of permanent residence was not lawful?

These doomsday scenarios may not come to fruition. However, it’s also possible they may lead to countless more rounds of litigation at the federal court level.

All legal practitioners would be well advised to contact clients whom they helped win permanent residency in the subject jurisdictions and forewarn them of the potential dangers ahead.

H-G-G Decision Slams USCIS Doors

Shut On TPS Lawful Status Periods

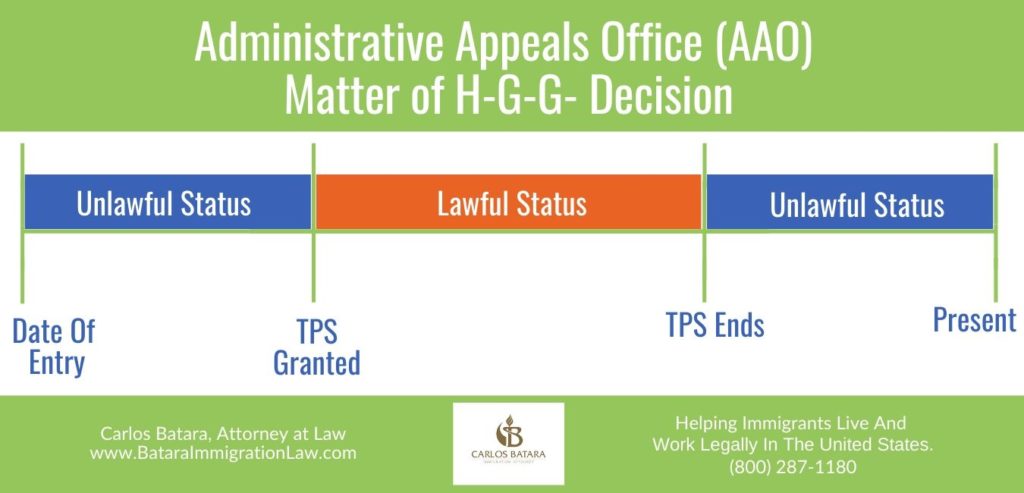

Prior to the Supreme Court ruling, the clearest expression why immigrants who entered the U.S. without inspection were not allowed a direct path from a grant of TPS to permanent residence was set forth in Matter of H-G-G.

In no uncertain terms, the Administrative Appeals Office (AAO) set strict parameters for USCIS offices in all states not under the jurisdiction of the 6th, 8th, or 9th Circuits.

Under the H-G-G decision, the AAO held that a grant of TPS does not:

- Confer lawful status for TPS recipients, except during the period that TPS is in effect

- Equate to an admission enabling beneficiaries to seek adjustment of status

- Cure periods of prior unlawful status, prior to the grant of TPS

Ironically, the H-G-G decision arose out of Minnesota, which is under the jurisdiction of the Eight Circuit Court of Appeals, a court in favor of granting TPS beneficiaries a road to legal residency based on TPS grants constituting the equivalent of lawful admissions.

With the tightening of the the noose around the lawful status period, H-G-G outlined how the TPS process worked.

Because a grant of TPS was not a lawful admission, according to the AAO, when TPS ends, recipients are returned to unlawful status.

In essence, this is the practical effect of the Sanchez decision.

Supreme Court Silence On USCIS Advance Parole Policy Shift Deepens TPS Woes

The Supreme Court decision did not address the third prong of the admission, inspection, and parole triad, the “parole” prong, as it relates to a TPS holder’s eligibility for adjustment of status.

This leaves the current USCIS interpretation on parole in place.

In 2020, rules governing advance parole, which had been in effect since 1991, underwent a silent policy shift.

At first, no formal announcement regarding this modification was issued. Yet, members of the American Immigration Lawyers Association reported TPS cases involving grantees who had received advance parole permission were in the past were suddenly denied that parole was equivalent to an admission and inspection.

In the past, if a TPS holder who initially entered the U.S. without inspection left the country temporarily under the approval of an Advance Parole Travel Document, the re-entry was deemed an inspection and admission. In these situations, having been lawfully admitted, the TPS beneficiary was eligible to seek adjustment of status.

USCIS offices had long held that immigrants who entered unlawfully, then went abroad

under advance parole, were considered to be returning in same immigration status they had at the time of most recent departure.

But suddenly, USCIS began to contend the status they were returning in was based on their original entry.

Upon arriving back in the U.S., their return is viewed as an entry without inspection for purposes of applying for permanent residency.

This seemingly subtle change was intended to impact TPS recipients living inside the 6th, 8th, and 9th circuits. They would no longer eligible for adjustment of status. Their re-entry was stripped of its lawful inspection and admission characterization.

This policy shift was finally articulated in the AAO’s Matter Of Z-R-Z-C- decision.

In that case, USCIS stated the policy change only applies to TPS recipients who left and came back to the U.S. under advance parole after August 20, 2020.

Their pathway to adjust status from temporary protected status recipient to permanent resident via an interview in the United States was blocked.

This is another matter that immigration lawyers will need to pay close attention to when helping past and present TPS grantees attempt to adjust status to permanent resident.

The Impact On Families: Love Happens Under TPS But Separation May Be Forever

Temporary Protected Status was enacted in 1990. The goal was humanitarian in nature.

Under the TPS program, immigration officers are allowed to grant immigrants from the designated countries with temporary refuge in the United States due to an environmental disaster, armed conflict, or other severe conditions.

It would seem that the adjustment of status for TPS beneficiaries to green card status, based on love and marriage, would qualify under any definition of humanitarianism.

However, for immigration officials, temporary for TPS has meant temporary. Even though the government never defined temporary.

As a result, the theme song for TPS beneficiaries seeking to adjust their status, over the years, may well have been an old tune by the Moments:

I found love on a two way street

And lost it on a lonely highway

Since the inception of Temporary Protected Status, immigrants living in the United States under TPS protections, like human beings across the globe, have been subject to the love bug at a moment’s notice.

They have established family and community ties. Recent estimates show that nearly 300,000 U.S. citizen children have at least one parent with TPS status.

Nonetheless, the government has not been willing to disregard requirements like unlawful entry or unlawful status for such individuals.

The net effect is to hinder efforts of U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident spouses to legalize the status of their spouses.

As noted above, the vast majority of TPS grantees can only seek permanent residency by returning to their home country for a green card interview.

Returning home is neither a welcomed or ideal solution for such families.

On the one hand, few TPS holders are willing to return home while the effects of the social chaos or natural destruction which led to the TPS designation remains unresolved.

On the other, TPS immigrants who travel abroad need to win an I-601 waiver to forgive the time they spent here without legal permission and be allowed lawful re-entry. If the waiver is not granted, they may be forced to remain outside the U.S. a long, long time – perhaps forever.

The Quest For A Rational TPS

Permanent Residency Continues

In my view as a San Bernardino immigration lawyer, the 6th, 8th, and 9th Circuit rulings reflected a dose of not only judicial rationality, but also human compassion.

For several years before these decisions, I privately asserted the government’s refusal to allow Temporary Protected Status grantees to become permanent residents was flawed.

On a case-by-case basis, I was able to persuade USCIS officers to accept my arguments. Still, I realized that the absence of a a system-wide policy adversely harmed far too many TPS beneficiaries and their families.

Unfortunately, the Supreme Court disagreed with my perspective.

To simply discard TPS recipients with long and productive lives spent in the U.S., coupled with deep family and community ties, is not a rational ending for a humanitarian program.

Yet, it appears no one in Congress considered how the TPS program would develop over the years. Thus, no one gave much thought to what happens to recipients when a grant of TPS is terminated.

A wholesale modification is still needed.

The Supreme Court decision in Sanchez v. Mayorkas was a major setback.

But it was neither absolute nor the final word.

I learned long ago that defeat in law, especially immigration law, should be taken with a grain of salt.

Policies and principles change over time.

Perhaps the Biden Administration will rise up and save the day with offsetting legislation.

In other words, the political, if not the legal, battle over TPS green card parameters is far from over.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics