To say that I was puzzled when I initially viewed the new USCIS policy guide on proving hardship for I-601 waivers is to understate my reaction.

It wasn’t based on the law.

Several months ago, when USCIS announced its intention to create hardship waiver guidelines, I went on record that I did not perceive any major additions or substantive changes forthcoming. After closer review of the new guidelines, my position remains unchanged.

On the contrary, I feared some of the proposed language could make it tougher to win hardship waivers.

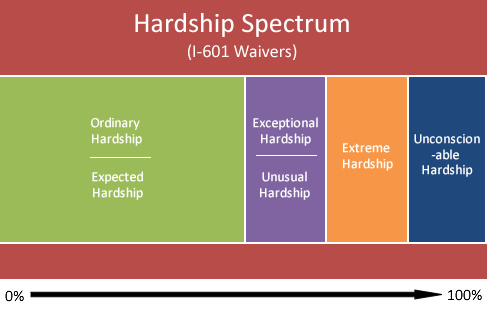

The USCIS I-601 Hardship Spectrum

My initial reaction to the USCIS I-601 hardship guidelines was perhaps too harsh.

As I noted in a Facebook commentary, I felt USCIS had mentioned a few new terms to describe extreme hardship – and these terms mumbled-jumbled the already existing terminology used to describe the level of suffering necessary to prove extreme hardship should be found.

In particular, the guide pointed out:

“USCIS recognizes that at least some degree of hardship to qualifying relatives exists in most, if not all, cases in which individuals with the requisite relationships are denied admission.”

The guide further noted, “To be considered extreme, the hardship must exceed that which is usual or expected. But extreme hardship need not be unique.”

At first, I thought “unique” hardship was being used as a quantitative term, helping to show the amount of suffering which immigrants must experience to win their cases.

But this interpretation was nonsensical. To the extent hardship is extreme, by definition, it is stronger than hardship which is unique.

On closer reflection, I realized the intended meaning of “unique” in the context of the USCIS hardship guidelines must be as a qualitative term. USCIS probably meant to explain that even though you and your friend have the same type of hardship – i.e., it’s not unique to you – it could still qualify as an extreme hardship.

(The USCIS explanation – that an extreme hardship need not be a unique hardship – is unnecessary, as well as partly confusing. Since the day-to-day situation of immigrants will never be the exact same, all hardship is at least minimally unique, even though the type of evidence two different immigrants present may be relatively the same.)

For years, I have used a spectrum of hardship to explain the difficulty of winning a case dependent on proving hardship.

- I started with a hardship graph for Suspension of Deportation cases.

- I added a graph for Cancellation of Removal matters, as hardship has been interpreted by the Board of Immigration appeals.

- Since I disagree with the BIA’s view in the latter situation, I also designed a graph to show what I believe is a proper reading of the exceptional and extremely unusual hardship.

- These three hardship spectrum graphs can be viewed here: Hardship Spectrum Graphs.

Now, with the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services finally putting some meat on its use of the extreme hardship terminology, I created a fourth hardship graph, illustrated at the top of this page.

I combined the major terms used by the recent USCIS memo with certain words, “exceptional” and “unusual”, which were added to the hardship lexicon by the Cancellation of Removal statute.

Throughout the design of these graphs, my goal has been to create a sense of consistency in the language used by the government throughout its various hardship permutations – thereby enabling immigrant families to understand the relative degrees of suffering needed to prove hardship.

In my view as a green card lawyer, the USCIS I-601 hardship graph – seen at the top of this post – reflects the most accurate visual portrayal of the hardship standard in use today for family unity waiver determinations.

Clearly, winning extreme hardship is not a simple matter.

It is contingent upon careful and tedious preparing, organizing, and presenting evidence of many personal, familial, and professional factors.

The New Factors Of Hardship Are The Old Factors Of Hardship

The more hardship factors are explained, the more they remain the same.

In fact, this is one of the primary reasons that I did not perceive any major additions or substantive changes would be provided in the new USCIS I-601 hardship guidelines.

A true assessment of hardship, after all, must be inclusive. It cannot exclude any real indicator of an individual’s suffering upon family separation.

The human mind, however innovative, cannot fathom all the possibilities that might arise in various cases with different families, of different sizes, with different life circumstances.

For those of us who practice hardship law defense, a three-prong approach to presenting such a wide variety of hardship factors has long been our guiding principle to organizing and presenting evidence on behalf of our clients:

Three Keys For The Evaluation Of Hardship

1. All relevant hardship factors must be considered.

It is not enough for adjudicators – judges or officers – to merely pay lip service to a wide range of factors bearing on hardship.

2. Each hardship factor must be evaluated individually.

Adjudicators are required to weigh the evidence presented by an immigrant, in a manner specific to that immigrant’s case, and not how such evidence generally affects immigrants from similar backgrounds.

3. The cumulative effect of all hardship factors must be assessed.

It’s rare, though possible, that any single factor on its own, or the hardship of any one family member by himself, can establish the requisite hardship to win a case. More often, the aggregate impact of various factors, upon the lives of various family members, leads to a determination of hardship.

Did the new USCIS I-601 guidelines add anything new to this three-step approach to analyzing factors of hardship?

Not at all.

In the words of USCIS, “To establish extreme hardship, it is not necessary to demonstrate that a single hardship, taken in isolation, rises to the level of extreme. Rather, any relevant hardship factors must be considered in the aggregate, not in isolation.”

“Even if no one factor individually rises to the level of extreme hardship, the USCIS officer must consider the entire range of factors concerning hardship in their totality and determine whether the combination of hardships takes the case beyond those hardships ordinarily associated with deportation (or, in this case, the refusal of admission).”

A False Criticism

As usual, the Center For Immigration Studies (CIS), an anti-immigrant rights organization, quickly portrayed the USCIS guidelines in a negative light, almost before the ink had dried.

Calling the guidelines a form of “definition creep”, CIS embarked on a lengthy discussion attacking the USCIS guidance that “now [c]larifies that factors, individually or in the aggregate, can be sufficient to meet the extreme hardship standard.”

Besides the falsehood that weighing factors in the aggregate is only now recognized as a means to demonstrate the requisite level of hardship, the Center wrongly asserts the new USCIS I-601 hardship guidelines are an attempt to fit ordinary and expected suffering into the definition of extreme hardship.

In other words, CIS reaches the same conclusion as immigration reform advocates: USCIS is reminding, if not mandating, adjudicators to assess hardship under a totality of the circumstances test.

However, CIS implies this approach to adjudication of waivers is new, and represents an effort by the Obama Adminstration to put as many worms into the immigration apple as they possibly can before leaving the White House.

The CIS View Of “Definition Creep”

Dan Cadman, CIS blogger, writes that In the Factors and Considerations for Extreme Hardship table of the guidance, under Economic Impact, he found clues as to when an adjudicator should determine that extreme hardship exists:

- Qualifying relatives‘ need to be educated in a foreign language or culture;

- Economic and financial loss due to the sale of a home or business;

- Economic and financial loss due to termination of a professional practice;

- Decline in the standard of living, including high levels of unemployment, underemployment, and lack of economic opportunity in country of nationality.

Cadman proceeds to question how these factors can lead to a finding of extreme hardship.

“Are these items truly so onerous as to constitute extreme hardship? I have my doubts. Many people relocating abroad, for instance to take a job they desire, find that they and their families need to develop new language skills and broader cultural horizons. This is neither unique nor extreme, nor even undesirable.”

“Likewise, employees relocating at an employer’s insistence to a new job locale, even within the United States, may find that they lose money on sale of a home, given the collapsed real estate market that never fully recovered from the Great Recession. And decline in the standard of living is certainly a strong possibility, given the great wealth of the United States compared with most of the world — but that is true of virtually every alien and family facing repatriation.”

“What exactly makes these things “extreme” as compared with the plight of other removable aliens similarly situated? If they are indistinguishable, how can they be a basis to grant a waiver (which should be the extraordinary exception, not the rule)?”

I agree with Cadman . . . in part.

I agree with him that these types of factors, in and by themselves, will not equal an extreme hardship in most cases.

But his analysis misses the point.

A true I-601 hardship analysis should be based on the totality of circumstances affecting the qualifying relative’s life upon the deportation of his or her spouse.

When such factors are combined with other factors, they are significant and should be considered by the hardship adjudicator. It’s the cumulative weight of all pertinent factors in a case which should guide.

Cadman’s sleight-of-hand attempt to disavow certain hardship factors by disconnecting them is misguided.

A finding of extreme hardship does not require each individual factor to be extreme.

Nor does each factor, as the USCIS I-601 hardship guidlines make clear, need to be unique.

Based on my experience as a San Diego immigration attorney, were these the criteria for assessing waiver applications, no immigrant could ever prevail.

Cadman asks CIS readers to think of the USCIS guidelines in this manner:

“No single family member exhibits sufficient hardship as to be described as extreme, and therefore there is no extreme hardship wall of sufficient size to act as a legal impediment to removing the alien. What to do? Deny the waiver? Well no, of course not. The guidance is telling adjudicators to see if they can build that wall with enough small pebbles aggregated from all of the family members. But that is not what the law specifies.”

Cadman is wrong, dead wrong.

Exploring the pebbles of a case is what immigration law has long asked judges, as well as agency officers, to consider in all cases, and not to arbitrarily deny the impact of any potential hardship factor, however small on its own.

Under a totality of the circumstances test, all hardship factors – including small evidentiary pebbles – are part of a valid family unity waiver application.

This is not new, contrary to many pro-immigrant pundits.

Nor is it, as opponents claim, a distortion of existing immigration law.

Making this point clear, if for no other reason, the new USCIS I-601 hardship guidelines are a positive step forward in the battle for compassionate immigration reform.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics