“Congress,” Justice Stevens once wrote, “like Humpty Dumpty, has the power to give words unorthodox meanings.”

So does the Board of Immigration Appeals.

Like exceptional and extremely unusual hardship.

I have few doubts, based on my experience as a San Diego immigration attorney in the 1990s, a Gingrich-led Congress wanted to impose a higher standard.

Yet, as Humpty Dumpty would tell both Congress and the BIA, the chosen words fall short.

Error 1: An Exceptional And Extremely Unusual Hardship Is Less Severe – Not More Severe – Than An Extreme Hardship

As explained in Why The Cancellation Of Removal Hardship Standard Is Unconscionable, the Board’s view of exceptional and extremely unusual hardship created an interpretative quagmire for immigration courts and lawyers.

In this post, I revisit my concerns and address additional mistakes in the BIA’s logic. I begin with a short return to the plain language of immigration hardship law.

According to the Board, under the shift to cancellation of removal, one of Congress’ goals was to define a hardship standard reflecting circumstances more severe than those of an extreme hardship.

Congress selected “exceptional and extremely unusual” hardship as the new standard.

An exceptional and extremely unusual hardship is not more severe than an extreme hardship.

Using plain language as our guide, here is what Congress’ definition means:

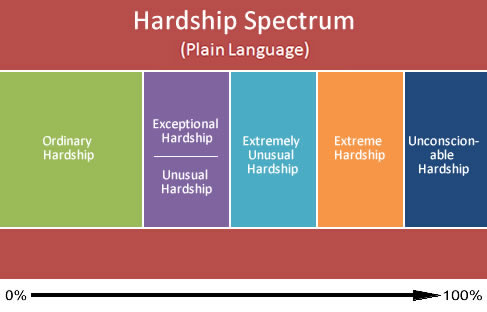

As the above graph shows, going from least severe to most severe, an exceptional hardship is less severe than an extremely unusual hardship, and an extremely unusual hardship is less severe than an extreme hardship.

Stated another way, an extreme hardship is more severe than both an exceptional hardship and an extremely unusual hardship.

In fact, since the terms “exceptional”, “extremely unusual”, and “extreme” describe increasing levels of severity, an “extreme hardship” is more severe than an “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship”.

This means, since the advent of cancellation of removal, immigration courts have adjudicated cases on a flawed analysis. They have reversed the core meaning of the words used by Congress.

For instance, in Matter of Monreal, the BIA concluded the respondent, Mr. Monreal, may have qualified for relief against deportation under an extreme hardship standard. But since his evidence did not meet the higher level of exceptional and extremely unusual hardship, he lost.

This is upside down thinking.

If Monreal qualified for extreme hardship – and this is more severe than exceptional and extremely unusual hardship – he should have won. Not vice versa.

In short, the BIA interpretation of the exceptional and extremely unusual standard is contrary to the plain language meaning of the words actually used by Congress.

Error 2: Congress Did Not Mandate An Exceptional And Unusually Extreme Hardship

The Board’s mistake, in part, lies in a failure to differentiate the meaning of an “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” from an “exceptional and unusually extreme hardship.”

Congress did not describe the new standard under cancellation of removal for non-lawful permanent residents as an exceptional and unusually extreme hardship.

This is an important point. So I’ll restate it.

Congress did not describe the new standard under cancellation of removal for non-lawful permanent residents as an exceptional and unusually extreme hardship.

Plain and simple, the current standard set by Congress, an exceptional and extremely unusual hardship, is not equal to an exceptional and unusually extreme hardship.

The distinction is not minor.

An exceptional and usually extreme hardship is more severe than an extreme hardship.

An exceptional and extremely unusual hardship is less severe than an extreme hardship.

By twisting the placement of a few words, the BIA distorted the cancellation of removal hardship standard defined by Congress for immigrants seeking relief from deportation.

Worse, by imposing an imaginary and unduly restrictive standard, the BIA’s error has led to the unjustified removal of thousands of immigrants since 1997.

Error 3: The Word “And” Does Not Mean “Plus” For Measuring Severity

Another aspect of the confusion surrounding Congress’ exceptional and extremely unusual hardship formula is the meaning of the word “and”.

Like many words, “and” has multiple meanings. The proper meaning depends on the context in which the word is used.

To better understand how “and” does not equate to “plus” in the context of cancellation of removal, we need to look at two different ways of measuring the severity of hardship to an immigrant’s family members.

The first method of assessment is to accumulate degrees of hardship. The second is to overlap them, where appropriate, to prevent duplication.

Accumulating Degrees Of Hardship

In the context of assessing hardship, “and” does not mean “plus” in a mathematical sense.

In an earlier article, I presented three graphs of hardship severity which show the different terminology used by courts to describe various degrees of hardship ranging from ordinary hardship to unconscionable hardship.

The degrees of severity suffered by an immigrant’s relative cannot be added like 2 + 2 = 4.

Logically speaking, whatever terms are used to describe the relative degrees of hardship, the maximum severity of an immigrant family’s hardship cannot exceed 100%.

Hence, to interpret “and” in a mathematical manner is disingenuous. Such an approach leads to a hardship standard greater than 100%.

Here’s such a process works.

Assume, in terms of severity, an exceptional hardship equals a 50% hardship. An extremely unusual hardship equals a 70% hardship.

By combining them as a “plus”, the total hardship is 120%.

As a matter of practicality, this is impossible.

In terms of deportation defense law, this assessment method sets the standard of hardship too high for any immigrant to ever reach.

This, of course, violates due process.

Yet, the “plus” approach is the form of analysis which has been used, subconsciously if not consciously, by courts in cancellation of removal cases since April 1, 1997.

Why Did I Choose 50% For An Exceptional Hardship?

The only hardship less severe than an exceptional hardship is an ordinary hardship.

So the key is how would courts define an ordinary hardship. It’s unlikely they would define it as much lower than 50%.

Most courts would fear if they assessed an ordinary hardship as having a severity factor under 50%, the floodgates would open and too many immigrants might qualify to cancel their deportations.

The lower the level of ordinary hardship, the lower the level of exceptional hardship. If ordinary hardship is 40%, then exceptional hardship is 45%.

Thus, in the effort to think like an immigration court judge, I choose 50% as the starting point for an exceptional hardship.

Significantly, even if my example used lower figures, the outcome would be similar.

For instance, if an exceptional hardship carries a 45% severity, and an extremely unusual hardship carries a 50% severity, that’s 95% when accumulated.

This is still an unconscionably high level of hardship and a violation of due process.

Overlapping Levels Of Hardship

There is another way to evaluate the standard of “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship.”

It’s a matter of duplication and overlap.

Under this approach, the use of the word “and” is meant to grammatically connect related words like “pencils and pens.”

To qualify for cancellation of removal, an immigrant must prove that his family’s hardship will be “exceptional” as well as “extremely unusual” if he is deported back to his home country.

Connecting the words in this manner does not artificially increase the level of hardship which must be proven by immigrants beyond the higher hardship standard.

An extremely unusual hardship subsumes and incorporates a less severe exceptional hardship.

Going back to the math example, a 70% extremely unusual hardship subsumes a less severe 50% exceptional hardship.

This means that the 70% hardship includes the 50% hardship (and then adds 20% more severity).

To win his or her case, an immigrant needs to show a hardship which reaches the higher level of severity, a 70% hardship.

Not an impossible 120%. (70% + 50%.)

It’s easy to understand why immigration courts have been unwilling to accept such an analysis.

By its choice of words, Congress either did or did not intend to impose a stricter standard.

The Board cannot have it both ways.

If Congress’ words match its intentions, the BIA is wrong about Congressional intent. An extremely unusual hardship is not as severe as an extreme hardship. To pretend otherwise is to deny the plain language rule of statutory construction.

If Congress’ words do not match its intentions, the BIA’s legal reasoning is flawed. The Board cannot accumulate the severity percentages of an exceptional and the severity percentages of an extremely unusual hardship. This leads to absurd results.

Either way, the BIA would be forced to admit their flawed interpretation of exceptional and extremely unusual hardship in cancellation of removal cases.

The BIA Hardship Legacy: Superflous Legal Words, Deficient Legal Decisions

So why, you ask, did Congress include the extra terminology?

Verbosity.

Lawyers are often excessive in drafting legal documents.

For instance, in the phrase “any and all” mistakes, does the word “any” describe mistakes not included in the word “all”?

On the other hand, does the word “all” describe mistakes not included in the word “any”?

Of course not.

For centuries, attorneys have used unnecessarily duplicative words to describe various situations.

Immigration law is not immune from attorney verbosity.

It’s hard to imagine, being an immigration appeals attorney, the Board is not aware of its hardship contradiction.

Instead, I’m inclined to think these errors are why the BIA has published only three decisions addressing the hardship standard under cancellation of removal, keeping deportation lawyers in the dark, since it went into effect.

That’s right. Only three decisions since April 1, 1997.

Meanwhile, immigrant families are destroyed by the thousands.

Immigration reform, anyone?

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics