When it comes to immigration law, what the Obama administration giveth, the Obama administration taketh away.

In mid-August, the administration announced it would suspend deportations against undocumented immigrants if they did not pose a national security or public safety threat.

The statement omitted any references to lawful permanent residents.

According to President Obama’s press statement, the goal of the new policy would be to identify and remove low priority deportation cases from the immigration system.

However, immigration reform talk by this administration is rarely reliable. Without concrete details, I suspected the press statement was just another cheap political publicity stunt.

My fears were not unfounded.

Not too long after the announcement, I was contacted by Ruxandra Guidi, KPBS Fronteras reporter.

She asked me to discuss another decision by the Obama Administration to file immigration appeals at the Supreme Court.

These appeals seek to overturn recent deportation decisions granting immigrants the right to remain in the U.S.

I was not surprised by the government’s action.

Nor amused by the contradiction between its two new policies.

A Political Tradeoff: Permanent Residents Vs. Undocumented Immigrants?

In particular, one of the cases, Holder v. Gutierrez, caught my attention.

The government sought to deport Gutierrez based on a minor offense. Gutierrez asserted he was entitled to relief under an immigration law known as cancellation of removal for lawful permanent residents.

The inconsistency was clear.

On the one hand, the government was willing to forego deportation efforts against immigrants with no legal status in the United States.

On the other, the government was adamant about pursuing removal proceedings against immigrants with lawful permanent resident status.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in support of Gutierrez.

The government objected, arguing he did not meet the requisite period of time necessary for lawful permanent residents to qualify for cancellation of removal. The disagreement centered on the relationship between parents and their children in the immigration context.

Does the parents’ time in lawful resident status count for the minor child?

Since I had successfully battled a similar admission issue from 1998 to 2006, I thought the smoke had cleared long ago.

Alas, it had not.

Cancellation Of Removal For Lawful Permanent Residents

When permanent residents are placed in deportation hearings, it is usually because they have been convicted of a criminal offense.

They are entitled to a hearing whether they should be given a second chance to live in the U.S. At the hearing, they have to show they meet the requirements for cancellation of removal.

To qualify, the green card holder must prove:

- He or she has been lawfully admitted for permanent residence for not less than five years

- He or she has resided in the United States for seven years after having been admitted in any status

- He or she has not been convicted of an aggravated felony

Even if a lawful permanent resident meets these requirements, this does not mean they win their case.

At the end of the hearing, the immigration judge must still decide whether the green card holder deserves to have his or her deportation cancelled, that is, deserves a second chance to live lawfully in the U.S.

If a serious crime has been committed, the immigrant will not meet the requirements.

The Ramifications Of Holder v. Gutierrez For Permanent Resident Families

The government appeal in Holder v. Guiterrez revolves around the first two requirements.

First, when can a parent’s years of lawful resident status be counted (“imputed”) to a minor immigrant child for purposes of fulfilling the permanent resident requirement?

Second, when can a parent’s years of lawful resident status be counted (“imputed”) to a minor immigrant child for purposes of fulfilling the admission requirement?

The relevant case history is short:

- Gutierrez and his family entered the United States illegally in 1988 or 1989. He was five years old.

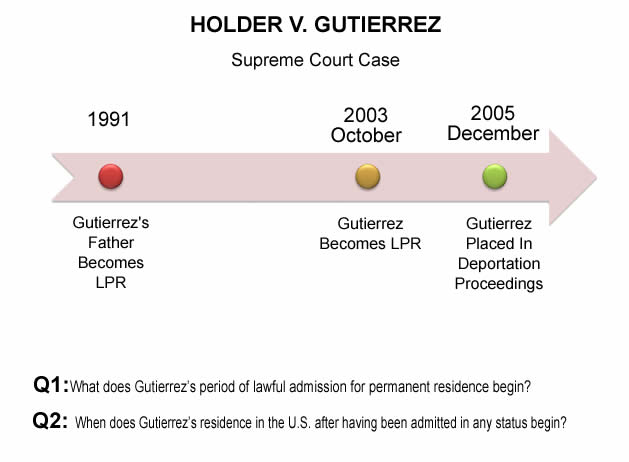

- In 1991, his father became a lawful permanent resident.

- In October 2003, Gutierrez attained legal U.S. residency at age 19.

- In December 2005, he was apprehended by immigration officials for committing a criminal offense. The crime was not an aggravated felony. He was placed in immigration proceedings.

During the immigration court hearings, the government argued Gutierrez should be deported because he could not meet the seven-year residence or five-year permanent residence tests mandated by cancellation of removal.

In the government’s view, since his lawful permanent residence started in 2005, less than five years before he was taken into custody and his immigration case started, Gutierrez is not entitled to immigration relief.

The immigration judge disagreed. She held that his father’s permanent residence should be imputed to Gutierrez. In her view, Gutierrez’s clock started in 1991, not 2005.

The consequences for Gutierrez are clear.

If Gutierrez cannot use his father’s permanent residence period, he loses. On the other hand, if he can use his father’s time, he wins.

The ramifications far exceed Gutierrez. The Supreme Court decision will affect immigrant families nationwide.

To Impute Or Not To Impute?

Being a proponent for immigrant family unification, I have mixed thoughts on the first question.

There are at least two ways to interpret “lawfully admitted for permanent residence.”

How the Supreme Court will rule is unclear.

If Congress had written “lawfully admitted as a permanent resident,” the interpretation would not be ambiguous.

Congressional writers should choose their words more carefully. Their meanings would be better understood.

In my view, as an immigration appeals lawyer, the permanent residence issue will be harder than the admission issue for immigration advocates to win.

Prior to reading this case, I felt the admission issue had been resolved long ago.

Thirteen years ago, I successfully argued Congress drafted the two separate provisions – lawful admission vis-à-vis permanent resident status – to designate two distinct ideas.

My views have not changed.

In other words, seven years of residing in the U.S. after having been admitted in any status is quite different from five years of lawful permanent residence.

Neither phrase is intended to qualify or limit the other phrase.

This is especially true for immigrants who became lawful permanent residents in the early 1990s.

At that time, it was common for many immigrants who earned a green card to file family visa petitions for their spouse and children through the family unity program.

Under family unity, an automatic stay of deportation went into effect once the immigration documents were filed. By granting an immigrant child the right to live here while their family petition was pending, the child obtained “lawful residence” in the United States after having been admitted.

Many years later, if everything went right, the immigrant child would become a permanent resident.

The fact that the admission issue is back up for grabs worries me.

Since the admission issue had already been resolved in the Ninth Circuit, the effort to stretch the meaning of the permanent residence clause was poorly calculated. Now, both issues are at risk.

In my experience, the admission provision is far more prevalent in deportation cases than the permanent residence issue.

A negative ruling could have grave consequences in many contexts beside cancellation of removal.

What if a immigrant is allowed to live in the United Status under TPS?

Or granted deferred action under the Violence Against Women Act?

Similarly, if the DREAM Act passes, immigrant youth would be granted temporary residence status.

Would these periods no longer count as a period of “lawful residence” for those who stumble into Gutierrez’s shoes one day?

The Danger Of Holder v. Gutierrez Beyond Cancellation Of Removal

As a Riverside immigration attorney, I sense the government’s latest action points to something far more disturbing.

The DREAM Act.

Immigrant youth who would qualify for the DREAM Act were brought to the U.S. at an early age by their parents. They had no input in their parents’ decision. They were too young to consent.

When the president claims he cannot use executive powers to help would-be DREAM Act beneficiaries, he often notes that the law-breaking acts of their parents cannot be easily forgiven.

In the government’s view, the sins of the parents are imputed to the children.

What’s good for the goose, however, is not good for the gander.

When imputing from parent to child benefits immigrants, the Obama administration files appeals to oppose imputing.

There is one common ground between these positions.

An anti-immigrant bias.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics