Facing deportation at immigration court, many undocumented immigrants learn about a “hardship” defense for the first time.

So what is hardship?

For most lawyers, it’s an easy concept to grasp. But difficult to explain.

In short, it means the negative effects which a person will experience if a loved one is removed from the United States. It’s the amount of suffering a parent, child, or parent will go through after an immigrant is deported or removed from the United States.

All deportations cause some degree of hardship.

Immigration courts, as a result, use a tougher standard to distinguish cases.

Ordinary hardship is not enough to win your case.

1. Before 1996: The Suspension Of Deportation Hardship Standard

As explained in an earlier post, Practicing Deportation Defense In The Dark, immigration law underwent a dramatic transformation in 1996.

A new law, commonly referred to as IIRAIRA (Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigration Responsibility Act) was passed.

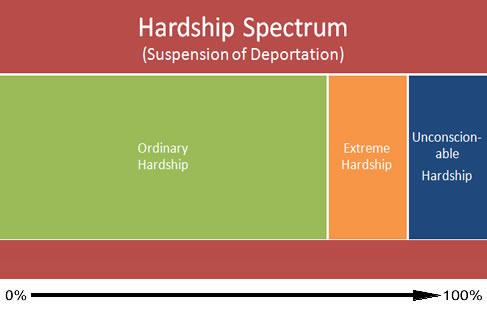

Prior to IIRAIRA, undocumented immigrants could request Suspension of Deportation. To win, they had to demonstrate “extreme” hardship.

Courts stressed that without a showing of significant or actual potential injury substantially different and more severe than that suffered by the ordinary alien who is deported, extreme hardship would not be found.

In my view as a deportation and removal defense lawyer, this explanation begs the question.

When is a hardship so severe that it is no longer ordinary? When does the suffering become extreme?

There is no clear line of demarcation. Rather, as the graph at the top of the page shows, extreme hardship is an issue which can be determined on a case-by-case basis.

Since the death of Suspension of Deportation, the already difficult-to-comprehend concept of hardship has become far more muddled.

2. After 1996: The Cancellation Of Removal Hardship Standard

Once IIRAIRA went into effect, a new hardship standard for deportation cases, now called removal cases, was imposed.

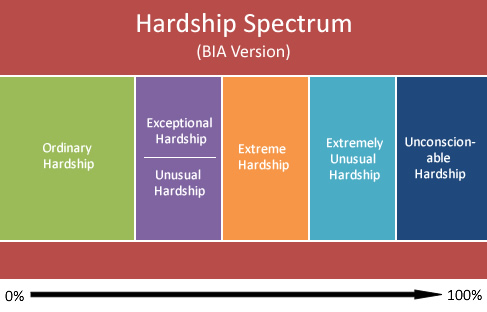

Under removal law, immigrants now had to demonstrate “exceptional and extremely unusual” hardship.

Even though IIRAIRA passed in 1996, immigration courts have still not clearly defined the newer standard.

In one of the few cases explaining the new hardship requirement, the Board of Immigration Appeals emphasized an undocumented immigrant must now provide evidence of harm to his spouse, parent, or child substantially beyond that which ordinarily would be expected from the alien’s deportation.

Strangely, this explanation for exceptional and extremely unusual hardship for Non-Lawful Permanent Resident Cancellation of Removal sounds almost the same as the explanation for extreme hardship under Suspension of Deportation.

According to the Board of Immigration Appeals, the two types of hardship are not the same. The newer hardship, exceptional and extremely unusual, is more severe than extreme hardship.

I disagree with the Board’s perspective.

3. A Plain Language View Of Hardship

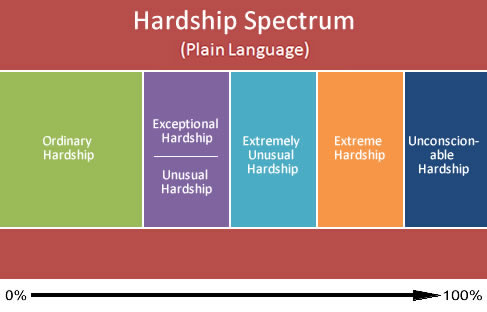

Immigration lawyers are taught to rely on the plain meaning of words when interpreting laws. When it comes to the issue of immigration hardship in deportation and removal cases, courts have overlooked this issue.

Based on the plain language of the words used, the word “extreme” connotes a condition more severe than either “exceptional” or “unusual”.

Due to this error, immigration judges are imposing stricter standards on immigrants than the law demands.

As shown above, my view of the proper hardship spectrum under Cancellation of Removal looks different than the one used by immigration courts.

It’s a point of distinction that, being a San Diego immigration lawyer, I have battled with immigration courts for over a decade.

Although I am bound to present cases using the BIA standard, I will continue fighting to correct this mistake.

Not only for past immigrants denied justice, but also for immigrants facing deportation in the future.

ByCarlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics