This blog post is Part 3 of our Mini-Series On Cancellation Of Removal for non-lawful permanent residents, an important component of our deportation defense services.

“Torn Apart,” blared the Riverside Press Enterprise. A front page story, the article described a family’s ordeal, whose mother was deported to her home country a few weeks earlier.

The woman, age 31, had lived in the United States since age 2. She was brought here by her parents, along with her brother, in 1979 with valid border crossing cards. The family was supposed to leave. Instead, they stayed.

Today, the woman is married to a U.S. citizen. She has four U.S. citizen children, three from a previous relationship. Her parents are U.S. citizens.

Before she was deported, she sought Cancellation of Removal. She lost at her immigration trial, and then lost an appeal.

The story is common to most immigrant communities across the nation.

Undocumented immigrants without legal permission to live in the United States are being detained and deported in record-breaking numbers.

A Policy Dilemma: Balancing Law Enforcement And Immigrant Family Needs

Whether immigrants, who enter our country without inspection or stay here beyond their authorized periods, should be allowed to ever become lawful permanent residents is one of the thorniest issues in our national immigration debate.

Most observers fall into one of two camps.

On one side stand advocates of tougher immigration controls. Mark Krikorian, director of the Center for Immigration Studies, notes, “It’s her parents’ decision that created this situation. They should have thought long and hard about the effect their decision would have on their children.”

On the other side, Crystal Williams, executive director of the American Immigration Lawyers Association, says, “Our country needs to have more compassion.” Echoing that sentiment, the deported woman’s mother adds, immigration officials “don’t see the lives of the people affected.”

The debate is not new.

Dating back to the early 1900s, our government has struggled with finding the proper balance between the law enforcement needs of immigration agencies and the human needs of immigrant families.

Unfortunately, the pendulum has swung back and forth depending on which way the political winds are blowing.

The Sliding Scale Of Immigration Hardship

After a period of unimpeded immigration between 1776 and 1875, immigration laws gradually grew more restrictive.

From 1917 to 1924, yearly quotas for each nationality were set in place. Once these limits were set, it was only time before the issue of undocumented immigrants would arise.

Over time, many immigrants, who had entered without proper permission or had overstayed their period of authorized visits, established deep family, work, and community roots. The blended families, comprised of both citizens and immigrants, became a normal component of the American landscape.

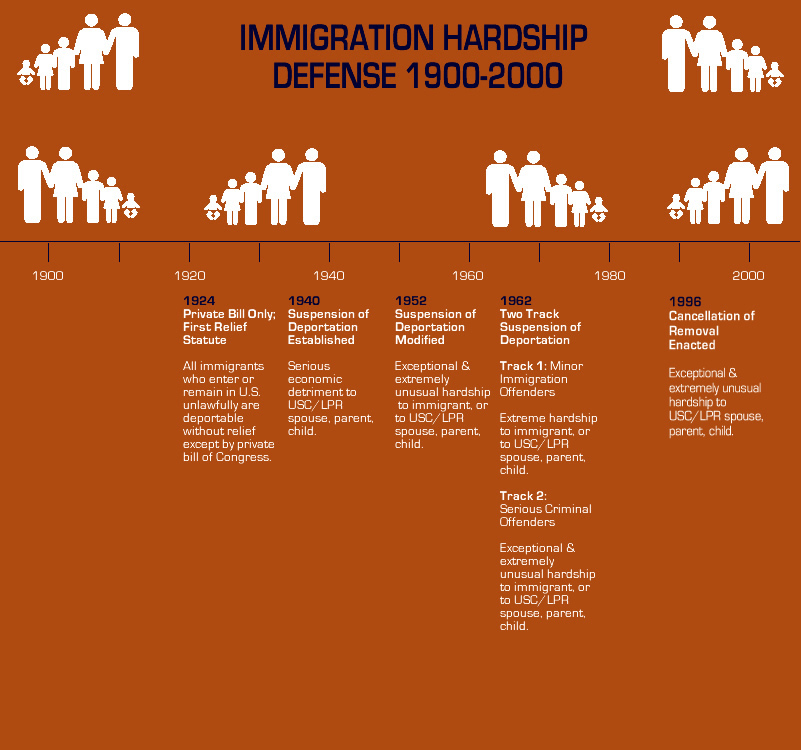

1924 – Private Bill Relief Only By Congress

The initial political response was rigid.

Under the Immigration Act of 1924, the Secretary of Labor was required to deport any immigrant who entered or remained in the United States unlawfully. An immigrant, deemed deportable, could only remain here by a private bill enacted by both Houses of Congress and approved by the President.

The odds of success for such immigrants were slim to none.

In essence, deportation defense was non-existent.

1940 – Suspension of Deportation: Serious Economic Detriment

As time passed, with the breakup of more and more blended families, calls for a more humanitarian approach to deportation became louder.

This led to the Alien Registration Act of 1940, the first statute providing immigrants with the opportunity to avoid deportation based on hardship.

The Act allowed the Attorney General to suspend an immigrant’s deportation if he could prove (a) five years of residence in the United States, (b) with good moral character during that period, and (c) that the immigrant’s deportation would result in “serious economic detriment” to a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident spouse, parent, or minor child.

In 1948, an amendment extended the availability of this relief to immigrants, even without family ties, if they could prove seven years of U.S. residence.

1952 – Suspension Of Deportation: Exceptional And Extremely Unusual Hardship

Anti-immigration critics, as one might expect, claimed the serious economic detriment test was too soft.

Congress responded, passing the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952.

Under the Act’s new provisions, immigrants could only prove they deserved a grant of Suspension of Deportation when their deportation resulted in an “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” to the immigrant, or to his U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident spouse, parent, or child.

House discussions were revealing on the extent of the restrictiveness:

“To justify the suspension of deportation the hardship must not only be unusual but must be exceptionally and extremely unusual. The bill accordingly establishes a policy that the administrative remedy should be available only in the very limited category of cases in which the deportation of the alien would be unconscionable.”

1962 – Two-Track Suspension Of Deportation: Extreme Hardship vs. Exceptional And Extremely Unusual Hardship

Eventually, the mood of McCarthyism gave way to the enlightenment of the Kennedy years. In 1962, Congress again revised the hardship standard under Suspension of Deportation.

The 1962 changes led to a two-track hardship system.

For undocumented immigrants facing deportation on less serious charges, relief depended on a showing of (a) seven years of continuous physical presence in the U.S., (b) good moral character, and (c) “extreme hardship” to the immigrant, or to his U.S. citizen or permanent resident spouse, parent, or child.

For those facing deportation based on more serious immigration and criminal violations, demonstration of (a) 10 years of continuous physical presence in the U.S., (b) good moral character, and (c) “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” to the immigrant, or to his U.S. citizen or permanent resident spouse, parent, or child was required.

This system stayed in place over 30 years.

1996 – Cancellation Of Removal: Exceptional And Extremely Unusual Hardship

In 1986, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) became law. Supported by President Ronald Reagan, IRCA opened various paths to legalization for undocumented immigrants who could meet the requirements.

Soon after, a xenophobic backlash began to call for the rolling back of benefits granted under IRCA.

In 1996, the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRAIRA) was passed. The law went far beyond IRCA’s positive benefits.

Among IIRAIRA’s harshest effects was the elimination of Suspension of Deportation.

In its place, Congress inserted Cancellation of Removal For Non-Lawful Permanent Residents. This tightened the requirements in immigration court for undocumented immigrants seeking relief from deportation.

To avoid deportation (now termed “removal”), all undocumented immigrants now had to demonstrate (a) ten years of continuous physical presence in the U.S., (b) good moral character, and (c) “exceptional and extremely unusual hardship” to the immigrant’s U.S. citizen or permanent resident spouse, parent, or child.

The immigrant’s personal hardship was excluded from consideration.

As discussed in The Congressional War Against Due Process At Immigration Court, several onerous provisions, such as prohibiting immigrants who committed certain non-violent, small offenses from any eligibility, were added.

This system remains in place today.

Immigration Policy By Political Wind Sailing

I began practicing as a San Diego immigration attorney under the two-track Suspension of Deportation system. Although it was far from perfect, it struck a relatively rational balance between important law enforcement and compelling human needs.

The same cannot be said for Cancellation of Removal.

When it comes to matters which drastically affect the lives of not only immigrants, but also U.S. citizens and permanent residents, riding wild wind currents is not a sensible approach to public policy.

For as Justice Louis Brandeis once wrote, deportation has the potential to deprive human beings “of all that makes life worth living.”

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics

You can find the other blog posts in our four-part Mini Series On Cancellation of Removal for non-lawful permanent residents here: