A few weeks ago, President Biden signed an executive order mandating a comprehensive review of the Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) programs for Afghan and Iraqi translators.

The announcement was overdue.

After risking their lives to help the United States, many loyal interpreters have been left stranded in an visa processing limbo and remain stuck in increasingly vulnerable living situations.

As the Washington Post noted, the U.S. government has neglected the urgent need to protect Iraqi and Afghan allies from retaliatory violence in their homelands.

All the while, the death toll of Afghan and Iraqi translators continues to grow.

An Inevitable Immigration Outcome Of

War In Afghanistan And Iraq

War is ugly.

The bleeding does not end with the final gunshot.

And the bill for it, as Benjamin Franklin once noted, comes afterwards.

Events in Afghanistan and Iraq confirm Franklin’s insight.

Once the U.S. military entered the Afghanistan and Iraq, I knew certain immigration outcomes seemed inevitable.

While most news stories and blog commentaries focused on the political and economic aftermath, I told anyone who would listen not to overlook immigration consequences.

In my view, it was unquestionable that another piecemeal addition to our hodgepodge quilt of immigration rules would be created.

I was not surprised when many decent Americans supported the idea that we needed to participate in rebuilding what we had destroyed. Nor was I stunned by the announcement of special immigrant visa programs for Iraqi and Afghan translators.

Yet, from the beginning, having watched (and participated in) the creation, implementation, success, and failure of numerous permanent residence endeavors as a San Bernardino green card lawyer, I sensed the SIV programs were fraught with potential trouble spots.

A Brief History Of Special Immigrant Visas For Afghan And Iraqi Interpreters

There have been three different programs for Iraqi and Afghan citizens who worked with the U.S. Armed Forces or Department of State in their home countries. The goal was to provide them a path to permanent residence in the United States with their families.

As I had suspected, having practiced as a family-based permanent residence attorney for three decades, problems surfaced early.

Iraqi And Afghan Interpreters

The first program for Iraqi and Afghan interpreters was created in 2006 as part of the National Defense Authorization Act. It set a cap of 50 visas per year and was limited to translators who had worked directly with the U.S. military. In 2007 and 2008 the cap was raised to 500, but in 2009 it was scaled back to 50 visas per year.

Iraqi Special Immigrant Visas

A more serious effort to help Middle East translators began with the passage of the Kennedy-Lugar Refugee Crisis Act of 2007. The bill established a new Special Immigration Visa classification for nationals of Iraq, authorizing 5,000 visas per year from 2008 to 2012.

To qualify, stringent requirements were outlined. Iraqis had to prove they had:

- been employed by, or on behalf of, the United States government in Iraq on or after March 20, 2003, for a period of one year or more;

- provided faithful and valuable service to the United States government, documented in a letter from his or her supervisor;

- (3) experienced, or be experiencing, an ongoing serious threat as a result of his or her United States government employment.

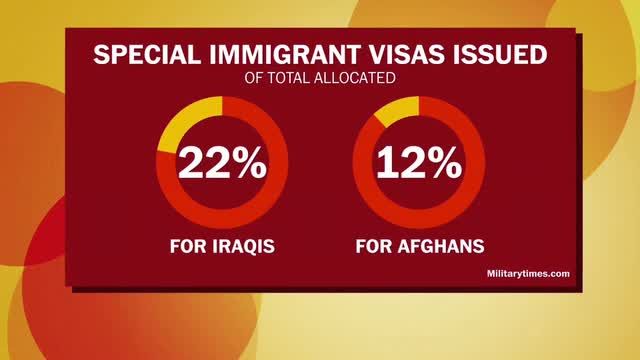

By 2013, only 5,500 special immigrant visas had been awarded. This represented a scanty 22% of total available visas for Iraqi translators and interpreters.

Afghan Special Immigrant Visas

In 2009, Congress followed up with a similar program for endangered Afghans who had worked for the U.S. government or military, on or after October 7, 2001 for at least one year. Entitled the Afghan Allies Protection Act, a total of 1,500 visas per year were allocated from 2009 through 2013.

Like its Iraqi counterpart, the Afghan special visa program did not meet its goals from the outset.

By 2011, only three visas had been approved. By the next year, the total had barely grown to 63. Six years after passage of the Afghan program, only 12% of the total available visas for Afghan interpreters have been issued.

The Military Times, a trusted voice for U.S. service members, produced the following chart to illustrate the obstacles facing SIV applicants at that time.

The Current Backlog And Dangers Facing Special Immigrant Visa Applicants

The approximate SIV waiting list for Afghans at present is 17,000. Coupled with their immediate family members, who also seek to move to the U.S., the Afghan waiting list increases to 70,000.

The backlog for Iraqis totals 100,000.

Given that Iraqi and Afghan translators are considered friends of “the American infidels” by the Taliban, ISIS, Al Qaeda, and other milita groups, it would seem the U.S. would have set up mechanisms to expedite their visa applications. Rather, the opposite has taken place.

Over 1,000 translators have been killed while waiting for visas to leave Afghan and Iraq.

Exposed to constant threats and violence, most worry that any day could be their last day.

And with diplomatic discussions taking place about a withdrawal of American troops, the liklihood of danger to U.S. loyalists is almost certain to occur.

Military advocates for former interpreters worry that time is slipping away from Afghan and Iraqi translators and their families.

If the U.S. withdraws, says retired Special Forces Maj. David Smyth, a decorated Green Beret who served four deployments in Afghanistan, “I don’t think it will be long before the Taliban takes over Afghanistan again.”

He adds, “If that happens, these guys are all targets.”

The original Congressional mandate specified a nine-month visa processing period. Yet, as noted above, even at the outset, under President Obama, this goal was not met.

Over time, the delays have grown worse. Under the Trump Administration, the average waiting period has increased to over three years.

As Deepa Alagesan, a senior attorney with the International Refugee Assistance Project, notes, applicants submit their paperwork “into a black hole” after which they hear nothing for two to three years.

The backlog is largely due to two major bureaucratic snafus.

One is a strict and cumbersome 14-step application process followed at U.S. Embassies in Kabul and Baghdad before a visa is granted.

In addition, emphasizes James Miervaldis, an Army veteran and chairman of the Board of Directors of No One Left Behind, a non-profit organization dedicated to ensuring America keeps its promise to interpreters from Iraq and Afghanistan, the government inefficiency is an interagency problem.

Three government agencies – the Department of State, the Department of Defense, and the Department of Homeland Security – own part of the process. The coordination is not smooth, leading to various administrative bottlenecks and lack of responsibility.

Such callousness is not new to U.S. foreign policy.

From its reluctance to assist the Philippines, a strong ally during war time, to its refusal to treat a loyal territory such as American Samoa as equal to other nations, our government often behaves as if political marriages are matters of short-term convenience, not long-term commitment.

The difference is this time, the would-be visa beneficiaries face death threats from hostile forces.

Thus, the executive order recently issued by President Biden was welcomed news by supporters of the Middle Eastern interpreters.

“A better executive order,” according to James Miervaldis, “could not have been hoped for”.

What Is The Biden Executive Order For Afghan And Iraqi Interpreters?

The Biden is an effort to identify the sources of of visa processing failures, interagency communication gaps, and bureaucratic delays that stretch for years.

A joint report assembled by Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin, DHS Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas is to be delivered to the president within six months.

The review will assess assess and provide recommendations regarding the following issues:

- Undue delays in processing applications, including those due to understaffing

- Training, guidance and oversight in processing of SIV applications

- Guidelines exist for reopening or reconsidering visa applications

- Procedures for cases where employer verification is not possible

- Ensuring effective anti-fraud measures are in place

Biden’s order recognizes that the U.S. cannot afford to continue this misguided approach in the Middle East.

In short, revamping the SIV program is critical to fulfilling our commitments to those who risked their lives, families, and homes to help defend the United States.

The interagency study is the first step in this process.

Why Not A Guam Option Solution?

In a Magic Valley editorial, the authors proposed a course of action utilized when Saigon fell in 1975 to communists.

More than 110,000 U.S. supporters from Vietnam, targeted for revenge when their regime collapsed, were brought to Guam. A processing center for immigration purposes was established, enabling Vietnamese citizens to complete the process of becoming legal United States residents.

By taking a similar action, Iraqis and Afghans who are experiencing an ongoing threat to their lives could be lifted to a safe haven. This would allow them to wait the lengthy red tape period bogging down the review and approval of special immigrant visa applications out of harm’s way.

Given the roles they played for U.S. troops in highly volatile environments, our Iraqi and Afghan allies deserve nothing less.

Honoring Immigration Promises: How Visa Processing Delays Harm U.S. Credibility

As one might suspect, there are those in Congress who fail to understand the value of political reciprocity, as well as minimize the fragility of the U.S presence in the Middle East.

Given irrational attitudes toward Arabs and Muslims, they prefer to terminate the Iraqi and Afghan interpreter visa programs.

During the last wave of Central American refugee children arriving at U.S. southwest borders, it was suggested that funds previously earmarked for the Iraqi and Afghan translator visas programs should be transferred to pay for the youth asylum claims.

Frankly speaking, this approach is wrong on both ends. Both issues demand a full and complete specific response from the U.S. government.

This short-sighted scheme overlooks American military personnel are still in Afghanistan. Others are in Iraq. If earlier translators are abandoned, few will seek such jobs in the future.

More significantly, to dishonor our permanent residency commitments to Iraqi and Afghan interpreters would send the wrong signal not just to our Middle East allies – but also to friends and foes around the world.

In other words, whether one agrees or disagrees with how the War On Terror has been handled, it’s time for all immigrant advocates to lend their support for those aspiring immigrants who bravely helped our troops during combat.

A promise, after all, is a promise.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics