Prior to April 1, 1997, Immigration and Nationality Act section 212(c) provided a waiver for certain lawful permanent residents who were rendered deportable by a criminal conviction.

But on that day, the constitutional promise of immigration due process dimmed, and deportation defense died.

Almost.

Left in a coma-like state by Newt Gingrich and his Congressional cronies, the concept of fairness in immigration law became a political farce, if not a national tragedy.

The implementation of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsbility Act (IIRAIRA), as noted in Newt Gingrich: The Grinch Who Stole Immigration Reform, was intended to eliminate nearly every avenue of legalization for immigrants.

At the time, I was an immigration lawyer in Escondido. I knew we had officially entered the dark ages of immigration law. There was no turning back. The gauntlet had been thrown down. It was fight or flight time.

Among the casualties, section 212(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Congress’ deletion of INA 212(c), a last chance defense, left many lawful permanent residents convicted of minor offenses without any means of relief against deportation.

Or so Congress thought.

Who Qualifies For Immigration And Nationality Act 212(c) Relief?

It depends, as in many areas of law, how the parameters are defined.

Section 212(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act has been at the center of deportation defense efforts for to prevent the deportation of lawful permanent residents convicted of relatively minor criminal offenses by plea bargains.

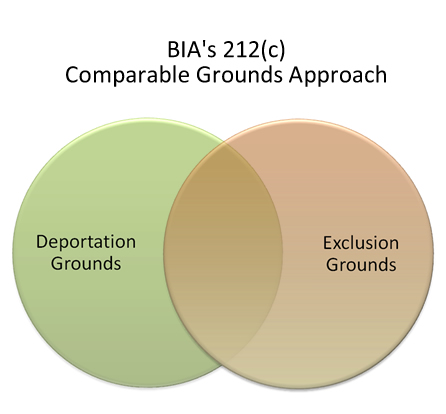

For several years, the Board of Immigration Appeals, the nation’s highest administrative body for interpreting and applying immigration law, had used the “comparable grounds” approach to decide which permanent residents are allowed to claim INA 212(c) as a defense against removal from the United States.

In the case of Judulang v. Holder, the Supreme Court rejected the BIA’s “comparable grounds” approach.

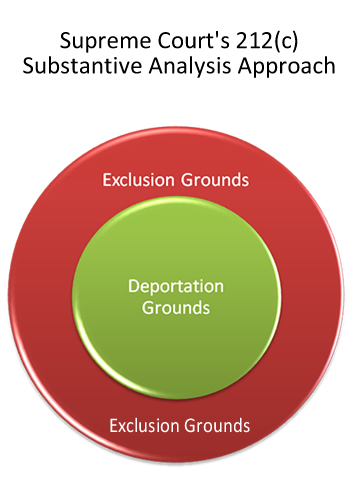

In its place, the Supreme Court substituted a “substantive analysis” approach to deciding how to evaluate the immigration charges against lawful permanent residents and determining who should be allowed to continue residing in the U.S.

The Deportation – Exclusion Distinction

In the eyes of deportation law, there are two types of immigrants. Those seeking entry to the United States. Those already here.

Pre-IIRAIRA, immigrants seeking admission to the U.S. were subject to exclusion rules. Immigrants living here faced deportation rules.

In reality, the division between the categories has never been a bright line. Because the rules for the two groups are different, the division at times has led to unfair treatment towards certain lawful permanent residents, usually those subject to deportation rules.

As a result, in cases dating back to 1940, the Attorney General was called upon to decide a lawful permanent resident detained inside the United States should have the same rights to relief as a lawful permanent resident detained at a port of entry upon returning from a trip abroad.

To do otherwise would constitute a violation of equal protection for similarly situation individuals.

This means a lawful permanent resident should be allowed the same ability to defend himself whether he faces deportation or exclusion.

In the post-IIRAIRA world, this terminology was changed. Immigrants seeking entry are now subject to inadmissibility, while those living inside the U.S. face rules for removal. Although the language changed, the concepts remain fairly intact.

The BIA’s Flawed Approach To Immigration And Nationality Act Section 212(c)

In 1974, Joel Judulang entered the United States as a lawful permanent resident. Born in the Philippines, he was 8 years old.

He has lived in the U.S. since that time. Today, he has a 14-year old daughter. His parents and two sisters are U.S. citizens.

In 1988, at age 22, he was involved in a fight. A victim was shot and killed. Judulang was not the shooter. He pled guilty to being an accessory to manslaughter. He received a 6-month suspended sentence and was released on probation.

17 years later, Judulang was taken into custody. The Department of Homeland Security. filed papers to deport him based on his 1988 conviction. He was charged with having committed an aggravated felony which involved a crime of violence. The immigration judge agreed.

He was ordered deported under immigration rules which did not exist in 1988.

In his immigration appeal, Judulang argued since his conviction took place before INA 212(c) was repealed by Congress, he was entitled to relief under the law in effect at the time of his conviction.

And under a 2001 Supreme Court decision, INS v. St. Cyr, he was correct.

However, in 2005, the Board of Immigration Appeals had engaged in a sleight of hand legal maneuver. They reverted back to the old distinction between lawful permanent residents in deportation and those in exclusion proceedings, twisting it in the context of post-IRRIARA rules and terminology.

Using a “comparable grounds approach,” the BIA denied Judulang’s appeal. They held Judulang was not entitled to rely on former INA 212(c). Since he was charged with a deportation ground which did not have a corresponding ground of exclusion, he could not use that provision of immigration law to defend himself.

According to the BIA, if a lawful permanent resident was charged under a deportation ground, he cannot seek relief under INA 212(c) – unless a similar ground existed under the exclusion rules.

Or so the BIA thought.

The Supreme Court Redefines INA 212(c)

On December 12, 2011, in Judulang v. Holder, the Supreme Court rejected the BIA’s approach.

In a rare 9-0 decision, the Court stressed a government agency’s actions which are “arbitrary, capricious, an abuse of discretion, or otherwise not in accordance with law” cannot be ignored.

If the scope of INA 212(c) is to be limited, the Court emphasized, it must be done in a rational way. The comparable grounds approach fails this test.

“The BIA asks whether the set of offenses in a particular deportation ground lines up with the set in an exclusion ground. But so what if it does? Does an alien charged with a particular deportation ground become more worthy of relief because that ground happens to match up with another? Or less worthy of relief because the ground does not?”

Staking out a new approach, the Court added:

“Or consider a different head scratching oddity of the comparable-grounds approach – that it may deny 212(c) eligibility to aliens whose deportation ground fits entirely inside an exclusion ground.”

Deportation, stressed the Court, cannot be made into a “sport of chance.”

Thus, the Court concluded:

”In reaching our decision today, we have been ever mindful of the fact that section 212(c) is, in essence, a forgiveness statute. It allows longtime lawful permanent residents to make a mistake, and to be forgiven for it in the immigration context, to keep his permanent resident status despite the mistake. It is a generous provision of the law and we believe that today’s action is fully in keeping with its generous spirit.”

How The Judulang Decision Has The Potential To Preserve Family Unity

Under Judulang, if a lawful permanent resident’s conviction can be classified under any ground of exclusion – even if its counterpart under deportation rules does not exist – he should not be prevented from seeking 212(c) relief from deportation

Over the past 15 years, lawful permanent residents have been trapped in the web of IIRAIRA’s changes to deportation defense law.

It is unknown exactly how many LPRs have been deported for convictions committed before 1996. Based on statistics cited in The Impact Of Deportation On Lawful Permanent Residents And Their Families, my estimate is that perhaps up to 50,000 LPRs have suffered this fate.

Had Judulang been decided, many of these deportations would have been averted.

So what does Judulang mean for lawful permanent residents already deported?

Some may be able to reopen their prior case and ask the court to reconsider their earlier ruling.

If someone you know:

- Was a lawful permanent resident

- Deported due to a criminal conviction

- Via a pre-1996 guilty plea bargain

He or she should consider consulting an immigration attorney to figure out if they were deported under the BIA’s flawed “comparable grounds” approach and whether they can reopen their deportation case under the Judulang decision.

Of course, battles to reopen will run into new hurdles imposed by government attorneys and immigration judges.

Nonetheless, for many separated immigrant families, this is a second chance which should not be passed up. After all, what’s there to lose?

A Small Step Forward In An Age Of Immigration Darkness

To be sure, Immigration and Nationality 212(c) is not simple to grasp for many persons untrained in reading legal statutes.

However, the two graphs shown above illustrate the differences between the BIA’s approach to evaluating 212(c) cases vis-à-vis the Supreme Court’s method of analysis.

This Judulang v. Holder decision is an important immigration appeals decision and a rare victory for immigrants in the current age of immigration darkness.

Since 1996, lawyers have fought to offset the harshly negative effects of the changes to immigration law brought forth by the passage of IIRAIRA.

Hence, if you know anyone trapped in the web of defending themselves under INA 212(c), study these graphs. Hopefully, they’ll provide an easier way for non-lawyers to grasp the different approaches used by courts in such cases involving permanent residents facing deportation due to convictions.

To the extent permanent residents comprehend these approaches, they may be able to improve their chances for winning and avoiding the pain and agony of family separation caused by deportation.

INA section 212(c) will not restore full due process to the overall functioning of our current immigration system. Although only a relatively small step, it is a major step forward in the battle for judicial fairness towards immigrants.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics