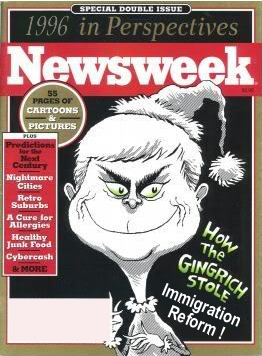

Newt Gingrich as the new savior of immigration?

Bah! Humbug!

Having practiced deportation defense in the 1990s, I am no Johnny-come-lately to immigration issues.

I remember the xenophobic backlash led by Gingrich against the 1986 Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) signed into law by a staunch conservative, Ronald Reagan.

I remember Gingrich as the Gin-Grinch who stole immigration reform.

The ramifications of actions taken by the Gingrich-led Congress reveberate throughout immigrant communities today – actions which laid the seeds for the excessive detention and deportation policies now in place.

Immigration Remorse Or Political Opportunism?

Writing in the Huffington Post a day after last week’s Republican Party primary debate, Pilar Marrero, a prominent Southern California journalist, outlined how Gingrich had talked about immigration in a manner uncommon for his contemporary political cohorts:

“I do not believe that the people of the United States are going to take people who have been here a quarter century, who have children and grandchildren, who are members of the community, who may have done something 25 years ago, separate them from their families, and expel them.”

“I don’t see how the party that says it’s the party of the family is going to adopt an immigration policy which destroys families that have been here a quarter century. And I’m prepared to take the heat for saying, let’s be humane in enforcing the law without giving them citizenship but by finding a way to create legality so that they are not separated from their families”

Like his political opponents, I was stunned by Gingrich’s comments.

Given his past efforts to destroy avenues of legalization, does he really expect any immigration advocates to believe him?

As Adlai Stevenson might put it:

“Well, Newt, it hurts too much to laugh. And I’m too old to cry.”

Newt Gingrich’s Immigration Legacy

In the view of some immigration activists, Gingrich’s statements herald a new beginning for immigration reform.

I don’t share that sentiment.

Over the past 15 years, as a San Bernardino immigration lawyer, I have witnessed the effects of Gingrich’s 1996 immigration reforms.

It hasn’t been pretty.

The Illegal Immigration Reform And Immigrant Responsibility Act Of 1996

As the Speaker of the House of Representatives from 1995 to 1999, Gingrich was a leading architect of the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRAIRA).

Many aspects of the current immigration debate can be traced to IIRAIRA. The legislation, part of Gingrich’s “Contract With America” agenda, was a repudiation of Reagan’s policies.

During this period, Gingrich and his cronies did not merely change immigration law. They transformed how the American public views immigration issues. They accentuated negative rhetoric, hostile imagery, and misleading arguments which now pervade the immigration reform debate.

Worse, IIRAIRA closed many avenues of defense against deportation for those trapped in the immigration court system. Countless lives of immigrants and their family members have been destroyed.

A few examples:

Asylum

After IIRAIRA, an immigrant seeking asylum was required to file his or her application for asylum within one year of arrival in the United States. The effect of this rule prohibits many asylum-seekers, fleeing political, racial, religious, or gender persecution, from being able to seek our protection against such abuses.

Expedited Removal

As part of IIRAIRA’s changes, expedited removal went into effect. This is a process where certain groups of immigrants can be deported from the United States without a hearing before an immigration judge and without any right to appeal or judicial review.

Suspension of Deportation

IIRAIRA eliminated Suspension of Deportation. For undocumented immigrants, this was often their only defense against deportation.

Prior to IIRAIRA, when undocumented immigrants living in the U.S. were apprehended, they could ask an immigration judge to suspend their deportation if they could meet certain requirements.

Applicants had to prove 7 years of continuous physical presence, during which he or she maintained good moral character. In addition, they had to show, if deported, an “extreme“ hardship would be placed on himself or herself, or a U.S. citizen or lawful permanent resident spouse, parent, or child.

In its place, Congress inserted Non-LPR Cancellation of Removal.

Under Cancellation of Removal, applicants now have to show 10 years of continuous physical presence, during which he or she has been a person of good moral character. In addition to the longer time frame, the list of convictions (many classified as minor misdemeanors under state law) which preclude a finding of good moral character was increased.

Moreover, a higher degree of hardship, “exceptional and extremely unusual”, was imposed on immigrants requesting Cancellation of Removal. At the same time, IRRAIRA mandated the personal hardship of an immigrant facing deportation could no longer be considered by an immigration judge.

As if those changes weren’t restrictive enough, IRRAIRA set a limit on how many immigrants could be adjusted to lawful permanent resident status via winning their Cancellation of Removal cases.

The cap was set at 4,000 per year.

In practical terms, since our immigration court system has approximately 250 judges, each judge is allocated about 10.5 positive Cancellation of Removal grants per year. That’s less than one favorable grant of permanent residence per month per judge.

Put another way, there are about 300,000 new cases entering the immigration court system per year. Assuming only one-sixth of these cases involve Cancellation of Removal, the 4,000 figure is tantamount to an 8% victory cap on total cases.

In reality, IIRAIRA set in place a system where judges award less than 4,000 affirmative cancellation decisions per year.

Immigration court statistics tell the story:

- 2006 – 3,138

- 2007 – 2.939

- 2008 – 3,028

- 2009 – 3,477

- 2010 – 3.982

INA 212(c) Relief

IIRAIRA also eliminated relief for lawful permanent residents under section 212(c) of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

Akin to Suspension of Deportation, the loss of 212(c) left many lawful permanent residents without any protection against deportation at immigration court.

Under 212(c), lawful permanent residents who had committed criminal offenses were given a second chance to remain in the U.S. To make such determinations, judges were allowed to weigh an immigrant’s negative equities – including the nature and seriousness of convictions – against his or her positive equities.

Once 212(c) was eliminated, judges were stripped of their authority to exercise discretion if an immigrant’s conviction fell into certain categories. For many permanent residents, this means automatic deportation, even if the offense was only a misdemeanor under state law.

As discussed in The Impact Of Deportation On Lawful Permanent Residents And Their Families, a joint University of California, Berkeley and University of California, Davis study showed the effects caused by the elimination of 212(c) from 1997 to 2007:

Lawful Permanent Residents

– 87,884 LPRs were deported during the ten year period

– 68% of these LPRs were deported for minor, non-violent crimes

– The deported LPRs had lived in the U.S. an average of ten years, long enough to form families

Children of Lawful Permanent Residents

– 53% of the deported LPRs had at least one child living with them

– 88,000 children of deported LPRs were U.S. citizens

– 44,000 children of deported LPRs were under the age of 5

Family Members of Lawful Permanent Residents

In addition, the study noted 217,000 other immediate family members – U.S. citizen husbands, wives, brothers, and sisters – were affected by the deportation of LPRs between 1997-2007.

The Obama Playbook?

In her article about the Republican Party debate, Marrero astutely noted “The former Speaker of the House . . . must have something he wants to achieve with this and I think he just took the first step.”

She added, “Maybe he´s planning a book about it or maybe he just wants to shake republicans from their illusion that they actually have a political future without the Latino vote.”

I think his motive is more basic.

It’s election season.

He is taking a page from the Obama playbook.

Sensing the desperation of immigration reformers to find someone to champion their cause, Gingrich, like Obama, is hoping lip-service commitment leads to an influx of supporters on election day.

And as with Obama, it’s up to immigrant advocates to reject the false promises of the Grinch who stole immigration reform.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics