Last summer I cheered when Padilla v. Kentucky was announced.

As a green card lawyer, I thought the Supreme Court had provided immigrants with a new weapon against unfair deportations.

Over the past 14 years, far too many lawful permanent residents have plead guilty to criminal charges without knowing the convictions would lead to automatic deportation from the U.S.

The Supreme Court Speaks

Like many immigration appeals attorneys, I would hear over and over again from immigrants, now facing removal at immigration court, that they were unaware they had signed away their rights to remain with their families.

Their criminal defense counsel did not advise them properly. In some instances, they were told the deal was “good” because it reduced the time they would spend in state jail.

However, they were not informed their conviction would be charged as an aggravated felony under immigration law.

They were not told what an aggravated felony meant under immigration law.

They were not told their good deal was actually an immigration death sentence.

They did not learn the true meaning of their good deal until after immigration agents took them into custody and placed them in detention at an immigration jail.

Often this took place 10 years or more after the guilty plea was signed, fines were paid, and probation was finished.

Once at the detention center, they were given papers by ICE officers seeking to deport them immediately back to their country.

Enter the Supreme Court.

“As a matter of federal law,” the Court said in Padilla v. Kentucky, “deportation is an integral part – indeed, sometimes the most important part – of the penalty that may be imposed on noncitizen defendants who plead guilty to specified crimes.”

The Court held immigrants have the right to challenge convictions that were based on flawed plea agreements.

If a plea bargain was the product of a constitutional defect, immigrants could go back to the state court to vacate the conviction and reopen their criminal case.

Justice Delayed, Justice Denied . . . Again

Unfortunately, the process of immigration recovery has been slowed by kinks in our system of justice.

They can be divided into four categories:

- Criminal Defense Attorneys

- State Court Judges

- Attorney Fees And Costs

- Immigration Court Procedures

Criminal Defense Lawyers: Lack Of Cooperation Or Compassion?

To win a motion to vacate a prior conviction requires showing how an immigrant’s earlier counsel failed to provide the proper advice about the immigration effects of pleading guilty to a specific offense. This puts immigrants at odds with their former attorneys.

Usually, an immigrant’s new lawyer reaches out to the earlier attorney.

Part of this approach is strategic. When both attorneys are on the same side of the fence, why take the risk of making the former lawyer an enemy?

The other part is practical. If the old attorney cooperates, it is easier to retrace what took place 5, 10, 15, 20 years ago.

Alas, compassionate cooperation has turned out to resemble a legal fantasy.

In case after case, attorneys who represented immigrants in the old cases become major obstacles in the new case.

Reluctant to admit they made a mistake, many refuse to cooperate with their former clients or provide ambiguous answers to questions raised by the new attorneys.

Of course, the older the case, the more everyone’s memory has faded.

Still, in cases less than a decade old, these former attorneys claim a loss of recollection, as well as a lack of notes to refresh their recollection.

Since several State Bar Associations have indicated such errors will not be considered professional malpractice, the lukewarm response of criminal defense lawyers is puzzling.

Rather than share information with an immigrant’s new attorney to fight for justice, they simply turn their back on their old clients – not acknowledging the role they played in their old client’s current predicament.

State Court Judges: Floodgate Phobia

Being an Escondido immigration attorney, I’ve learned another stumbling block immigrants face in trying to vacate prior convictions are state court judges.

In some cases, state judges have set excessively high standards of evidence on permanent residents trying to eliminate their earlier convictions.

Despite the Supreme Court’s mandate, these judges are not willing to concede immigrants deserve a second bite of an apple even when the first apple was rotten.

Recently, a criminal defense colleague shared how one judge became visibly upset by a motion to vacate. “Without compelling evidence,” the judge told him and his client, “I refuse to open the floodgates for illegal immigrants to escape the full scope of their punishments.”

This attitude is not new.

In various cases reported across the country, the decisions of state judges denying efforts to vacate prior convictions have been overturned by higher courts for flawed reasoning.

Worse, in some instances, when cases have been sent back to state judges to change certain aspects of their ruling, judges have refused to follow the appellate court’s lead. Rather, they modified their original decisions only slightly, stretching facts to reach the same conclusions again.

When the personal views of a judge trump legal principles, the phobia of open floodgates has gone too far.

Supreme Court Tightens Floodgates

On February 20, 2013, the Supreme Court of the United States took on the issue of immigrant floodgates, limiting the reach of Padilla v. Kentucky.

In Chaidez v. United States, the Justices held that its earlier decision did not apply to immigrants whose convictions had become final by the time of their decision in March 2010.

The court’s ruling restricts non-citizens from seeking to overturn a bad guilty plea, from an immigration defense standpoint, based on claims of ineffective assistance of counsel, if their conviction was finalized prior to the Padilla opinion.

The case involved an immigrant from Mexico, Roselva Chaidez, who had been a legal permanent resident since 1977. In 2003, she pled guilty to mail fraud and was sentenced to four years of probation. She was never told by her criminal defense lawyer that the plea could result in deportation. Thus, she accepted the plea, blind to the immigration consequences.

Six years later, in 2009, she sought to naturalize. Instead, her citizenship application was denied and she was placed in removal proceedings at immigration court.

Although a federal judge agreed with Chaidez’s position and set aside her conviction, the government challenged the ruling. On appeal, the Supreme Court overturned the lower court’s decision.

The Economic Costs Of Justice

For many immigrants, the financial cost of vacating prior convictions is more than they can afford.

Generally speaking, in Southern California, criminal defense attorneys charge between $10,000 and $20,000 for such services.

That’s only for the first round.

If an immigrant happens to have his case heard by a judge afraid of opening floodgates, an appeal will more likely than not become necessary.

That’s more fees.

If the immigrant succeeds on appeal, the case will usually be remanded back to the state judge.

That’s more fees.

In the meantime, the immigrant is still in deportation proceedings and needs the help of a removal defense attorney.

Again, that’s more fees.

In other words, justice for immigrants remains elusive for those who cannot afford its price tag.

The Immigration Court’s Retreat From Padilla v. Kentucky

Usually, permanent residents who are picked up and detained by ICE several years after their convictions are considered aggravated felons.

As discussed in The Impact Of Deportation On Lawful Permanent Residents And Their Families, the majority were guilty of nothing more than state misdemeanors . . . committed 20, 30, 40 years ago.

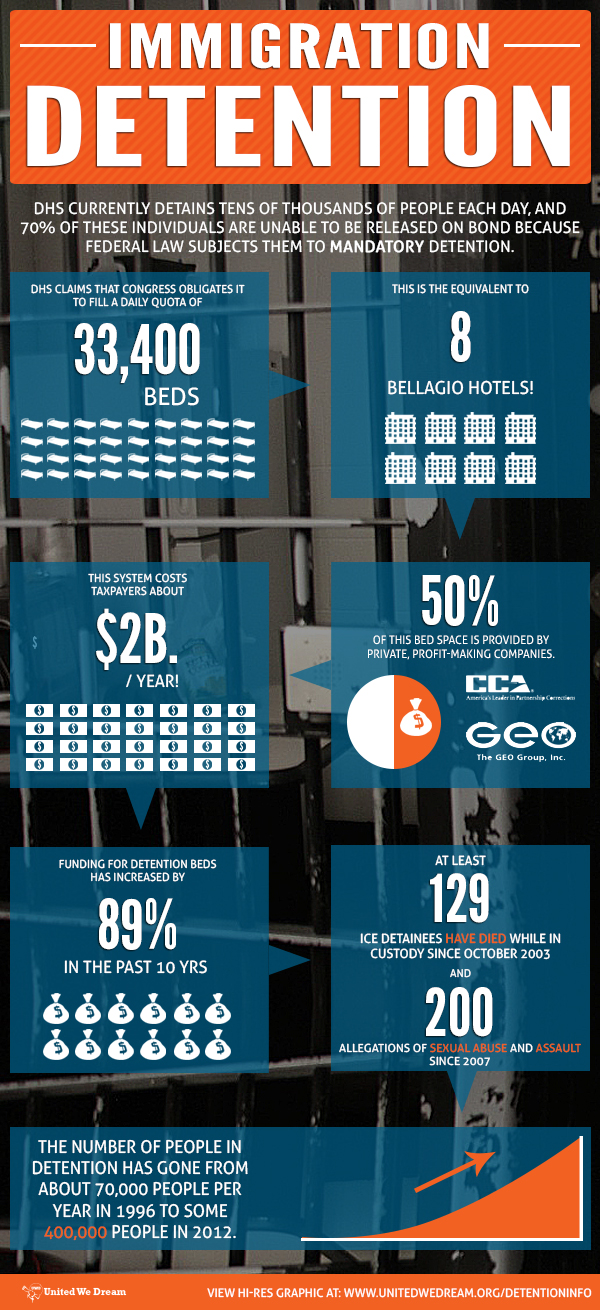

Being classified as aggravated felons means they are likely subject to mandatory detention. They will not be entitled to an immigration bond hearing or allowed to post bond.

Custody is a major impediment to victory.

Few, if any, individuals want to remain locked up at a detention center for weeks, months, perhaps years – at the same time their loved ones are paying thousands of dollars to fight deportation.

And that’s only for the families who can afford the fees to fight.

There’s more.

Immigration judges and government attorneys are not willing to delay hearings long enough for immigrants to contest their convictions at state court. Despite Padilla v. Kentucky.

In their view, the past conviction is a final conviction.

In the mid 1990s, when Congress stripped permanent residents of rules allowing them to fight deportation after committing certain offenses, they also took away immigrants’ rights to defer deportation while the constitutional defects of the same convictions were being addressed in state court.

But if immigrant detainees are not allowed time to go back to state court, there is no way to fight the conviction. And if there is no way to fight the conviction, there is no chance to avoid deportation.

Such outcomes are not the outcomes of blind justice . . . nor the outcomes envisioned by the Supreme Court.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics