What’s the number one cause of the breakup of immigrant families when the immigrant parent is a permanent resident?

Aggravated felonies ?

Failure to naturalize?

When I’ve posed this question at public forums, critics attempt to undermine its importance by suggesting it asks the immigration equivalence of whether the chicken or the egg came first.

Actually, it’s doesn’t.

Rather, their knee jerk response reflects a reckless indifference towards the failure of lawful permanent residents to take actions to ensure family unity.

The question raises a serious issue which immigrant advocates need to address with the immigrant families they purport to serve.

As a San Bernardino immigration attorney, I’ve learned that far too many immigrants who have become lawful permanent residents fail to apply for naturalized citizenship. Too often this leads to the separation of husband from wife, parent from child.

Any time deportation separates a parent from loved ones, the outcome is traumatic for all involved.

Why, then, do many green card holders neglect naturalization and risk such adverse consequences?

A brush with the law is not going to get a citizen deported, except for very rare circumstances.

Lest anyone gets confused with my position, I am not suggesting this is the only reason immigrants should become citizens.

Rates Of Naturalization By Ethnic Groups

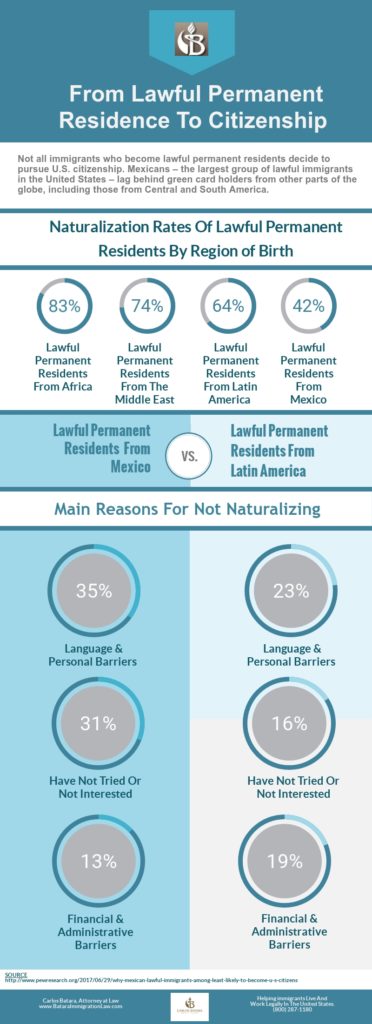

As one might suspect, the rates of such non-action varies by ethnic groups.

Ironically, a recent study by the Pew Research Center found that of green card holders who become U.S. citizens, the numerically largest immigrant group, immigrants from Mexico, had the lowest rate of applying for naturalization. A mere 42% apply for naturalized citizenship.

The study found that lawful immigrant residents from the Middle East are the most likely set of green card holders to become U.S. citizens, with 83% applying for naturalizing.

In second, legal permanent residents from Africa seek U.S. citizenship at a 74% rate.

Even immigrants from other Spanish-speaking countries in South and Central America participate at a higher rate than their language brethren. They apply at a 64% rate.

I admit, despite providing citizenship and naturalization services for over two decades, the findings surprised me.

The study went on to explore why there was such a great disparity among Mexicans and other Spanish-speaking communities.

It found that whereas 35% of Mexican permanent residents cite language and personal barriers as the dominant cause for not seeking naturalization, only 23% from South and Central America claim this is their primary excuse for not attempting to become U.S. citizens.

A bigger differential emerged for those who cited “have not tried or not interested” as their main rationale for not moving to the final frontier of U.S. immigration law. Although 31% of lawful residents from Mexico noted this as the main factor for their failure to naturalize, only 16% of those from Latin American said this was their top reason for not starting the process to naturalize.

Permanent Residence And The Lingering Danger Of Family Separation

Despite all the positive reasons to become a U.S. citizen, there is one overriding negative factor which it seems would propel those with green card status to take the next step.

That’s the risk of deportation.

Even though citizens can be denaturalized, the process is far more complicated and less common than the deportation and removal of immigrants from the United States.

A few years ago, research by the University of California at Berkeley and the University of California at Davis showed during a 10 year period, over 60,000 permanent residents had been deported for committing minor non-violent crimes (classified as “aggravated felonies” under immigration law).

They left behind 103,000 minor children. 88,000 were U.S. citizen children. 44,000 were under the age of 5.

10 Year Study By UC Berkeley And UC Davis

- 60,000 Lawful Permanent Residents Deported

- For Minor, Non-Violent Offenses

- The Deported Permanent Residents Had 103,000 Children

- 88,000 Of These Children Were U.S. Citizens

- 50% Of The U.S. Citizen Children Were Under 5

There is no reason to presume the deportation rate of permanent residents has slowed in recent years. Indeed, the opposite is most likely accurate under the current presidential administration.

What this means is that the vast majority of these children will grow up without their father.

Some families, upon deportation to a parent, relocate to the country of the deported immigrant, as discussed in Deportation And U.S. Citizen Children: The Impact Of Relocation. When this happens, the U.S. born children usually suffer grave setbacks educationally and emotionally.

Not exactly an ideal solution.

In either situation, the message should be clear to permanent residents. Don’t test your luck by remaining in resident status your entire life. As soon as you’re eligible, apply for naturalization.

Many of the family heartbreak suffered due to convictions for minor, non-violent crimes could have been avoided had the permanent resident parents become citizens.

And, of course, staying out of trouble also helps.

Do The Dreamers Hold The Key To Increased Citizenship Rates Of Mexican Immigrants?

Will the rate of Mexican permanent residents who file citizenship applications increase in the future?

After all, under the Trump Administration, there has been a heightened interest in seeking to become naturalized citizens among all immigrant groups.

That’s a temporary reason for an uplift.

As a 20+ years’ veteran handling permanent residency and citizenship cases, I think there is a potentially huge reason why the Mexican immigrant rate may increase. The young folks, the DACA folks, the Dreamers. They want to become full-fledged members of American society. Once they find a path to legalization, I think they will in large numbers move from green cards to citizenship.

This trend may take five, ten years to materialize. Let’s keep our fingers crossed.

The Failure Of Permanent Residents To Naturalize: Why Play With Fire?

Video Transcript

In today’s Immigration LIVE Tidbit, I’d like to discuss a recent study conducted and published by the Pew Research Center. It focused on the rates of naturalization by immigrants who have already become lawful permanent residents.

The study found that of the various regions of the world, those immigrants who became lawful permanent residents from the Middle East had the highest participation rate. Their rate was 83 percent.

In second were immigrants from Africa. Their rate of participation from lawful residency to naturalized citizenship was 74 percent.

But what the study really pointed out was the very low rate of participation from lawful permanent resident to United States citizenship by Mexican immigrants who had become lawful permanent residents.

By contrast, the study also analyzed Hispanics from other Latin American and Central American countries to discern if they had the same low rate of participation.

They did not. The study found that 64 percent of eligible non-Mexican Hispanic immigrants go on to become United States citizens.

Okay, that’s enough statistics for now.

I want to move on to why I think the issue of not moving forward of becoming a United States citizen is extremely crucial.

An individual came to my office just yesterday. He had been a lawful permanent resident for over 20 years. He had a few United States citizen children that were minors. He had been in trouble with the law several years ago for some minor non-violent offenses. However, because those minor non-violent offenses can still be classified as aggravated felonies under immigration law, this can become a problem.

And for him, it was one because he has been called, summoned, to the immigration court.

That’s part of the Trump administration’s move to use old convictions and to find people with old records that they can now attempt to deport.

Anyway, he’s not alone.

A study about three or four years ago, a joint study conducted by the University of California at Berkeley and the University of California at Davis, found that over a ten-year period, about 60,000 lawful permanent residents who have lived in United States for ten years were deported for minor non-violent offenses over a ten-year period.

Here’s what’s really significant.

They had 103.000 minor children, of which 88,000 were born in the United States, and half of them, 44,000, were under the age of 5.

What I have found in my practice is that a lot of times individuals who visit my office arrive in the same situation as the person who visited me the other day.

They are often the one person in their family who did not become a United States citizen.

So when this person came to my office the other day, I naturally probed him on that subject. And lo and behold, that’s exactly his situation. All his brothers and sisters, many years ago, had went on to become United States citizens. He had not.

And so now he is at risk to be deported for what you and I, and many other Americans, would consider minor offenses. He is certainly not deserving of deportation, but because of the nature of the offenses, they were drug offenses, he stands the risk of being deported and separated permanently from his minor United States citizen children.

That’s the danger when individuals who are lawful permanent residents do not take the next step, do not go to what I call the final frontier of immigration law, and naturalize. That’s the danger.

There’s one other point about the study that I’d like to point out.

I think that in future years, the percentage of Mexican immigrants who become lawful permanent residents and then decide to become United States citizens will rise. And it’s not due to a temporary reason like fear of the Trump administration, although I think probably the 2017 statistics will bear out that he has driven a lot of people to become United States citizens who otherwise would not have.

I think the real reason for a major shift upwards will be the DACA folks, the Dreamers.

It’s to me that they want to be full participants in American society. Many of them want to run for office. Many of them want to become full-fledged college professors. Many of them want to become lawyers, doctors, and accountants.

I believe that as time goes on, and they will move on to become lawful permanent residents. I think eventually most of them will find a path to residency and they will move forward and become United States citizens.

And in the future, this will drive up the permanent resident to citizen rates. At least, that’s my hope.

By Carlos Batara, Immigration Law, Policy, And Politics